ANOTHER EXCEPTIONALLY WET WINTER HIGHLIGHTS THE BENEFITS OF GOOD SOIL STRUCTURE AND DRAINAGE.

Following another extremely wet winter Jeff Claydon, a Suffolk farmer and inventor of the Opti-Till® direct strip seeding system, talks about the importance of good soil structure and drainage. He also discusses the initial results of stubble management and cover crop trials on E. T. Claydon & Sons’ arable enterprise.

20 February 2021

Following the extremes of weather and associated challenges which most farmers had to deal with during 2019/20, one might have hoped that the law of averages would mean that this season was easier. So far at least, that has not been the case. With such extremes becoming increasingly frequent, clearly, we must position ourselves to deal with them by ensuring that our soils are in optimum condition and that we use an establishment system which significantly reduces our exposure to weather risk.

Statistically, Suffolk is one of the driest counties in the UK, but even here, after a scorching summer when temperatures peaked at 36°C, we still ended 2020 with 700mm of rain. Of that, over 400mm fell between harvest and the end of December, which has been a challenge on our very heavy Hanslope series chalky boulder clay soils that are notoriously difficult to manage. When wet, they can become impossibly sticky, unfriendly, and slow to drain, but when dry set like concrete. At either extreme they are impossible to work, so all field operations must be carried out within a very narrow time window and when conditions are exactly right.

Until mid-October, our soils remained dry enough to absorb the persistent and often heavy rainfall, but the wet weather continued throughout the autumn and winter. Our weather station next to the Claydon offices recorded another 146mm during January and 46mm in the first two weeks of February, making this one of the wettest winters on record. Driving around the area over the last few weeks I have passed many fields that are in poor condition after being over-worked, or where inappropriate machinery was used at the wrong time. Some were waterlogged, slumped, and capped, worm activity was minimal, crops which had been drilled were stressed and even weeds refused to grow in some areas. Elsewhere, topsoil had been washed off fields, causing crop loss and polluting water courses.

As I write this during the third week of February, we have experienced two weeks of extremely cold weather. The plume of Arctic air that the media dubbed ‘The Beast From The East’ caused temperatures to plummet to a low of -15°C with the windchill factor. The cold snap may have passed, but the wet weather shows no signs of abating and our crops are at their most depressed point in the growing cycle. However, unlike many, they are all set to flourish once the mercury starts to rise.

Every week I talk to existing and prospective Claydon customers throughout the UK and overseas, so I know that many of you also operate in extremely challenging situations and need a robust establishment system. Because of the Claydon Opti-Till® System’s ability to establish any seed that can be air-sown, in all soils and conditions, using around 16l/ha of diesel even on our heavy clay soils – about 10% of that required for a plough-based system – it is now being adopted not just by arable producers but increasingly those in the dairy sector for crops like grass, maize and stubble turnips. With the current talks of reducing CO2 to much lower levels and increasing carbon capture, we are ahead in this field.

When you next have a few minutes to spare you might like to watch ‘The first year of Claydon direct drilling on a UK dairy farm’, an excellent video which Charlie Eaton, Claydon’s Territory Manager for the South and West of England, made over several months on a farm in the Cotswolds. Visit the Wiltshire section of the UK video gallery on our website www.claydondrill.com – it’s well worth a look. Our website video galleries also have numerous videos on soil health and resilience, as well as of the Claydon OptiTill® System being used to establish all types of crops, in all situations, both in the UK and overseas. You can also keep up with the latest posts, photographs, and videos from Claydon and our customers through the Claydon Facebook page (www.facebook.com/Claydondrill). It’s also a great place to share, discuss and question what you are seeing on your farm with other like-minded individuals.

Time to check soils

Extremes of weather such as we have experienced during the last two seasons highlight the importance of having resilient soils with excellent structure, supported by an effective drainage system to take water away. Spring is the ideal time to take stock of your soils, test how good they are, look for signs of compaction, and check that the drainage system is operating correctly. This can be done easily and cheaply using nothing more complicated than a fork, penetrometer, water infiltration tray and a couple of jam jars if you really feel like pushing the boat out to do a Slake Test! With this information you can then plan to correct any deficiencies.

When assessing soil condition, the first thing I do is to carry out several penetrometer tests across the field to check there are no soil pans, as these will severely limit drainage and root development. If they are present, the probe becomes much more difficult to push into the ground and the indicator needle swings into the red. Pans are not caused solely by compaction from heavy machinery or working when conditions are unfavourable but can result from the sedimentation of soils that have been over-cultivated and ‘settled out’ over the winter.

This is clearly demonstrated with the Slake Test, which provides an excellent indication of a soil’s resilience and health, is easy to do and costs nothing. Briefly, it assesses the stability of soil aggregates when exposed to rapid wetting, as in the case of heavy or prolonged rainfall. The slower the soil breaks up the better as this indicates that it contains a high degree of organic matter which helps to bind it together. You can see this simple yet important test being carried out on the Claydon farm by Dick Neale, Technical Manager for Hutchinsons, in a short video on the ‘Soil’ page of our website.

Good drainage is essential

One cannot talk about soil health and resilience without discussing drainage, an area of soil management that is fundamental to good soil structure but often neglected. You don’t need me to tell you that well-drained soils go hand in hand with healthy soils and high yields. The key is to ensure that drains are adequate to cope with the highest flows and well maintained so they don’t become blocked or have their capacity reduced and become overwhelmed during periods of heavy, prolonged rain.

Since land drainage grants finished in the 1970s many farms have been unwilling or unable to invest in new schemes. Four decades on, many existing ones have become obsolete and ineffective, which is a major blow because effective drainage helps soils to dry out and improves timeliness. It also makes them easier to manage, enables fertilisers and ag-chems to work most efficiently and minimises leaching, not forgetting that it also typically leads to yield improvements of 25%-30%. Recent studies have confirmed that new land drainage systems on average can start to pay for themselves after eight years.

If, after heavy rainfall, the water flowing from field drains is dirty this indicates that it is full of sediment, so your valuable soils are literally going down the drain, increasing the risks of soil erosion and flooding. This sediment will also block worm holes and capillaries, killing worms, starving the crop’s roots of essential air and nutrients, reducing yield potential, and ultimately increasing the cost-pertonne of production. Most of the Claydon farm is drained and after two decades of using OptiTill® our soils are very well structured, so water permeates freely. Nevertheless, the drainage system has been pushed to its limits this season. In January, for example, we had one day when over 35mm of rain fell, which overburdened the field drains and water coming out of the pipes ran cloudy. A small amount of overnight surface ponding was also evident in a couple of areas, so I will want to address this in the months ahead by installing additional laterals.

Some have the fear that well drained land increases the flow rates, which to a point it does, but they do not consider the sponge effect of well drained land, where the water is gently filtered through the soil and released steadily, unlike waterlogged soil which washes off the top at a time when we need to achieve clean water to drain and a healthy environment. Healthy soil copes better with these extremes due to the increased presence of soil biota, and our high organic scores on the farm have certainly proved their worth in recent weeks. Driving past some fields where conventional full cultivations and mintill systems have been used, you can see the results of overworked soil which has had its structure destroyed and worm populations adversely affected. It can easily be seen in the last two years where the wrong equipment has been used in wet, adverse conditions. Degrading the soil in this way also reduces its ability to drain water away during extended periods of wet weather and increases capillary action moisture losses in dry conditions.

Given increasing public interest in countryside and environmental issues, including soil erosion, Defra would do well to reinstate drainage grants and fund attenuation ponds to catch sedimentation, as well as to control the release/flow of water. This could be a base for future management strategies considering the weather patterns of the last couple of years. Their work should also address both the capacity and condition of river systems, the need for adequate maintenance of ditches, and give more recognition to the role of correctly structured and managed farmland in holding water and releasing it gradually to prevent water courses from being overwhelmed, leading to flooding.

Stubble management and cover crops

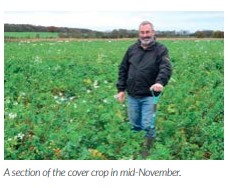

In the last issue of Direct Driller, I outlined the trials we are conducting to evaluate different approaches to stubble management and cover crops, in the same field, under the same conditions. Even at this early stage they have provided plenty of food for thought. The field next to the Claydon factory which we allocated for this is part of 55ha destined for sowing with WPB Elyann (KWS) spring oats, a crop which is easy and relatively inexpensive to grow but often produces a margin on a par with winter wheat. Some of the area was straw harrowed up to four times then left, while on 10ha we drilled a cover crop using different methods to see if, and by how much, it improves the yield and overall margin from following crops. The yield from each area will be measured so we can assess the agronomic and financial impact.

Cover crops are still relatively new in the UK, with most farmers and agronomists still learning about what does and does not work. The trials have been very revealing, but as the lockdowns, sadly, have greatly restricted travel and prevented us all from holding public events you can watch a video of Dick Neale, Technical Manager for Hutchinsons, discussing our cover crops on the video gallery of the Claydon website at www.claydondrill.com

We used Hutchinsons MaxiCover, a general-purpose over-winter cover crop mix containing linseed, buckwheat, phacelia, daikon radish, fodder radish, brown mustard, hairy vetch, and crimson clover. Costing £35/ha, it was drilled at 12.5kg/ha on 9 August using three seeding options on our 3m Claydon Hybrid test drill. With a few simple, quick, low-cost modifications any new or existing Hybrid drill can be used for conventional sowing, lower disturbance establishment and zero-till seeding, with or without fertiliser placement between or in the seeded rows, directly into stubbles, chopped straw, cover crops and grassland. This makes it a versatile, costeffective solution.

In one area we used the standard Claydon Opti-Till® set-up comprising the leading tine which relieves compaction and aerates the soil, followed by a seeding tine with a 20cm A-share. In another we used the leading tine followed by our twin-tine kit. The third was drilled with the new lower-disturbance ‘LD’ twin-tine kit preceded by double front cutting discs which reduce power requirement and minimise soil disturbance. In all cases the cover crop produced a mass of roots. The diversity of species in these mixes means that, regardless of weather, soil conditions, field aspect and establishment methods, it produces a viable cover crop, because even if a couple of species do not thrive because conditions are not right for them in that situation others will grow. Having various plant canopy profiles provides good soil armour and weather protection which has a positive effect in terms of controlling grassweeds, as well as further improving soil condition.

The heavy calcareous clay soil on the Claydon farm has a high calcium base which attracts phosphate and locks it up, so crop roots can have difficulty in accessing this vital nutrient. Buckwheat, one of the species in the MaxiCover mix, produces acids which help to release phosphate and so it plays a valuable role in achieving a correct soil nutrient balance. Ideally, we want the cover crop to be in the ground long enough to gain maximum advantage from the rooting structures, but not so long so that it generates excessive stick-like biomass. The original idea was that cover crops would be sprayed off at the end of November and those areas left until spring, when we will drill spring oats directly as soon as conditions allow. However, we decided instead to graze some off with a neighbour’s small flock of sheep and then rolled the cover crop area with our 12m Cambridge rolls around Christmas on a small frost.

The cold weather of recent weeks has broken down almost all the top biomass, so we will have no issues with it shielding grass weeds from an application of glyphosate applied before drilling. Neither will we have any problems sowing spring oats into the heavy soil, which can be very wet and cold with too much green cover, and this should allow a perfect seedbed environment. The cover rooting has been retained with high levels of worms, so it will be interesting to see how the different areas behave in the following crop.

Obvious differences

With our rotation having changed from wheat and oilseed rape to include more spring-sown and break crops, the aim is to use land destined for spring drilling to help reduce the weed burden and seed bank using Opti-Till® stubble management techniques which move no more than 2cm of topsoil. This will enable us to control weed seeds and volunteers without herbicides, other than one fullrate application of glyphosate just prior to drilling. Effective stubble management has become particularly important following the loss of neonicotinoid seed treatments and some products to control grassweeds as there is a fear that the aphid vectors of Barley Yellow Dwarf Virus (BYDV) will increase significantly. This can be reduced considerably by using Opti-Till® to manage stubbles and eliminate the green bridge effect. It also enables drilling to be delayed, but to do that with any degree of certainty you must be able to get the crop in the ground quickly, which means not having too many operations before sowing.

It has been fascinating to compare the effects of two, three and four passes with the Straw Harrow, a fast, low-cost operation, under identical conditions. This has highlighted the effectiveness of this technique and the significant benefit of using more passes. The differences are as clear as day, as can be seen from the accompanying photographs. We also have numerous videos about stubble management on the Claydon website.

In the next issue of Direct Driller, I will look at how each of the trial areas drilled in the spring and talk through any differences that were apparent at that time.