Is the adoption of IPM (integrated pest management) a journey? A journey of change required to react to changing market demands; a journey of learning, stemming from wanting to do something different to protect natural Beneficial’s and predators; a journey to increasing profitability from the production of a crop grown to an IPM enhanced standard? Teresa Meadows, Nuffield Scholar 2020, shares her thoughts as she sets out to look at this topic in more depth.

The start of my global Nuffield journey has shown these themes developing through the conversations held with farmers, growers, consultants, researchers, CEO’s and organisations across the world. I am looking at how we can learn from these people and practices around the world to be able to increase the uptake of integrated pest management in the arable sector back here in the UK. Embracing the virtual world over the last few months, I have had the pleasure of speaking to people both at home and abroad from the comfort of my home office. I have spoken to those who are long established IPM practitioners, such as Andrew Watson, cotton grower of Australia; those that are carrying out research so that an IPM approach can be adopted, such as Sarah Mansfield, researcher on pasture pests in New Zealand or those that are taking those practices out to the field, such as Vinod Pandit, running the Plantwise programme in Nepal.

The conversations from Bangladesh to Switzerland and the US to Germany have covered crops including leeks, cotton, pumpkins, tomatoes, onions, pasture, cut flowers; protected glasshouse and field crops and every conversation has been had with someone with an enthusiasm and a passion for the topic of IPM, in its different guises. There have been so many highlights already and many conversations that have served to provoke or change thinking. A selection of these are included below…

Putting IPM at the start and heart of a programme

Fargro’s IPM specialists, Neil Helyer and Ant Surrage (www.fargro.co.uk/) work hard with their horticulture growers on creating IPM programmes – putting cultural control and biological approaches first and at the heart of what they do…and only using chemical approaches as a last resort. Can we change our mindset in the arable sector to design an ‘IPM programme’ for our crops, rather than a ‘fungicide/ herbicide programme’? There are lots of good examples of IPM being employed across our sector, but do we bring this together as a holistic IPM programme at the centre of what we do for everything, and name it that? Perhaps not quite yet?

Monitoring to increase understanding

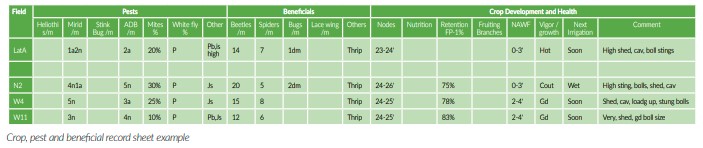

Andrew Watson, cotton and arable farmer in Australia (Twitter: @bugs_r_ us) has driven the use of recording through the season, not solely of crop growth stages, but also of pests and natural enemy levels and has gained so much value for the business from this approach. His weekly cotton recording data, consisting of plant mapping (height, number of branches, number of fruit) is collected alongside insect profiles and these are charted against the rising levels of pests and beneficials. The knowledge of this interaction has allowed an increased understanding of the levels and the natural fluxes, moving from an average of 3-4 insecticide sprays per year to only having one year that they have had to spray the farm since 2007 and trying new approaches and technology, such as releasing beneficials from drones above the crop. Could/should us as farmers or our agronomists or advisors be monitoring pest and natural enemy levels for our arable crops and using the outcomes to make decisions? We are good in many instances at monitoring the pests, but do we monitor the beneficials to the same degree?

A structured programme of advice and extension

Vinod Pandit who runs the Plantwise ( h t t p s : // w w w . p l a n t w i s e . o r g / ) programme across South East Asia, including Nepal, India and Bangladesh attributes much of the success of the initiative to the structured programme, formed of three main fields:

1. Plant health system – formed of the Plant Clinics run by their Plant Doctors at the forefront, where rural villagers can go to get their information, diagnosis of samples and advice.

2. Knowledge Bank – an online information system with the latest research, articles and tools to support those on the ground with technical information

3. Monitoring and evaluation – to see what actions have been successful and what has been delivered on the ground, which can then be used for continual improvement.

With Plantwise partners in 33 countries and 9,200 Plant Doctors based in these countries, the successful implementation is attributed by Vinod to the strong extension system and easy implementation using the knowledge system to back-up advice and guidance. Can AHDB and others across the UK arable advice sector follow a similar structured programme, bringing together existing knowledge, information and programmes into something that is widely recognised as the “go-to” place for information, advisors running a structured programme of extension and the programme continually evaluated and improved?

The incentives

Abdullah al Shakib, an independent research consultant in Bangladesh, recently evaluated a behaviour change programme with 50,000 smallholders in rural communities in the country. The discussions about the main reasons for change through these programmes rang true for many of our experiences and discussions – the impact of effective knowledge sharing in communities, the need for independent advice, the use of ‘lead farmers’ in a community, but also the positive impact of a financial incentive.

Abdullah went to two districts as part of his work, where the programme was working to influence the introduction of integrated pest management. He found that in one area, the farmers had seen a 200-300% improvement in their practices. In the other area, this was only 30-40% increase above the baseline. Abdullah was very interested, why, with the same kind of interventions, one area performed so well against the other lower performing one.

In the area not performing well – they smallholders were selling to local traders and local fruit shops, so the prices were low and they weren’t receiving any agronomic information from the buyers. In contrast, in the area with high performance levels, the smallholders were able to link with big buyers and big chain stores, such as Agola, who were purchasing their vegetables, as well as their milk. So, when purchasing, the buyers would say, “you can give me the pumpkin, but it has to be a weight of 1.5kg and this colour and if it reaches this specification, you will get 30-50% more price…”. This agronomic information helped with the growing of the product and these new practices were then implemented and rewarded by a higher price.

Abdullah’s conclusions were that in every business, you need to show incentives – either a cost reduction, increase in productivity or increase in price…or a combination. Conversations with Abdullah and others surrounding incentives, centred on the financial reward, reduced business cost or increased market access from the use of IPM measures. Can this financial compensation be created in the UK arable sector to add extra incentive for the widespread uptake? How important is this factor vs others – I am interested in looking into this further as I proceed in the conversations.

The Nuffield journey has started, the conversations around integrated pest management and facilitating the widespread uptake of these practices have begun, themes are emerging and conversations naturally lead to more questions, avenues to investigate and more passionate, articulate and enthusiastic people to talk to. To follow my Nuffield journey, please see my blog posts on LinkedIn or keep a track via Twitter (@CerealsEA).