Written by David Boulton of Indigro

Born out of an industrial and intensive era, ‘regenerative’ and ‘regeneration’ are the newest buzzwords to describe a forward movement in agriculture.

By definition, regeneration is the process of restoration – to develop and improve something, making it as good or successful as it previously was. In an agricultural context, it is a holistic approach to improving farmland, by enhancing natural ecosystems and working with nature. At its core is the protection and restoration of the soil, the quality of which is the foundation for agricultural productivity and environmental resilience.

Following the agricultural revolution in the early post-world war period, landuse changes and the intensification of soil cultivations and synthetic product use has led to the provision of plentiful and cheap food, to meet the needs of an expanding population – but at what environmental cost? Agricultural efficiency has increased, with generally larger and more specialised enterprises. However, permanent pasture has been converted into continuously cultivated arable regimes and the use of pesticide and synthetic fertiliser has increased.

This current system faces many challenges, including widespread pest resistance, agrochemical and nitrate contamination of water, increasingly stringent plant protection product regulations, soil erosion and declining farm biodiversity, to name a few. We have reached an economic and environmental tipping point and require a more positive direction of travel.

The principles of regenerative farming

There is no single regenerative blueprint that will work on every farm and soil type, and each site will have its own unique challenges and opportunities. For example, poorly drained heavy clay soil will not be conducive to delayed winter cereal sowing or planting a spring crop after grazing a cover crop with livestock in marginal conditions. There are, however, several underlying principles. Soil cover must be maintained, by returning crop residue and establishing catch and cover crops between cash crops. Miniature (small leaved) white clover can be very successful in providing a permanent, nitrogen fixing understory, that can be grazed by sheep when not in a crop.

Maintain a wide and diverse rotation (including the use of different cover crop species) to control weeds, pest and disease, utilising winter and spring crops. Use companion crops where possible, especially in oilseed rape, to provide diversity of root architecture and to capture nutrients.

Utilise organic manures and amendments, such as compost, digestate, biosolids and farmyard manure. These are not just excellent sources of crop available nutrients but also improve soil structure and build soil organic matter. Having livestock enterprises can help add another income to the business and are an excellent way of destroying cover crops. In conjunction, aim to cut down manufactured nitrogen use, because this will help to significantly reduce the carbon footprint of the farm, and will also make crops less dependable on other inputs such as fungicides and growth regulators.

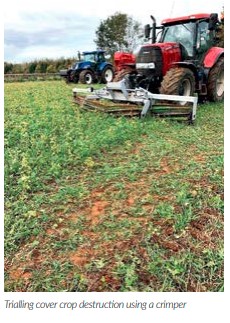

Crop establishment should revolve around minimal soil disturbance. Since regenerative farming is not a prescribed approach, farmers and land managers have the ability to decipher and select which technique will suit their system the best. Either a low disturbance tine or disc drill may be appropriate, based on soil type, blackgrass pressure and cover crop destruction approach. A further aspect is following the principles of integrated pest management (IPM) and using this process when making any agronomic decision on a crop.

Current constraints

A key question hangs over the dependency of the regenerative system on glyphosate. This broad-spectrum herbicide plays a crucial role in the destruction of problem annual and perennial weeds, such as blackgrass and couch grass and is also a dependable means of terminating cover crops and grass and clover leys. Alternative chemical molecules and weed control strategies are being considered and will most definitely be required. The destruction of cover crops can be successfully achieved using crimper rollers, livestock, toppers, and with some assistance from consecutive hard frosts. However, selecting the right species in the cover crop and timing of destruction is vital.

There are also challenges with making the system work on poorly drained, heavy soil types, which incur low yields, inefficient resource use and nitrous oxide emissions. The yielddrop in the transition period, dealing with compaction and managing the decomposition phase of the nutrient cycle when cover crops are destroyed are key aspects that require further understanding.

Managing risk by farming for the environment

Farming regeneratively, is intrinsically, farming in a manner that supports the natural environment. Working together, the implementation of countryside stewardship can help to reduce the financial risk of the system, particularly where there is a yield decline in the first few years of transition and facilitate the improvement to soil quality.

Options such as legume and herbrich swards, buffer strips and winter cover crops compliment the aims of a regenerative farming system and provide a fixed income, irrespective of turbulent weather and commodity market pressures. With the Environmental Land Management scheme on the horizon, I would like to see greater flexibility with regards to the management and implementation of stewardship options, and further collaboration of neighbouring farmers to provide large scale environmental benefits.

The direction of travel towards carbon offsetting

The regenerative model places growers in a unique position to both lower the greenhouse gas emissions of one’s own farming business and sequester the emissions from other industries and businesses. At present, there is no standardised accreditation for the process of carbon sequestration via land management in the UK, however, a ‘soil carbon code’ or similar scheme will facilitate the trading of carbon credits.

Potential incentives from government could be coupled with voluntary market initiatives, stacking the monetisation for land managers of regenerating their soils and farmed landscape. The challenge for the industry will be how best to measure and quantify successful outcomes for accreditation. Most likely, it will be a combination of satellite imagery and geospatial soil organic matter sampling.

A knowledge and collaboration driven approach

Being a holistic approach, the knowledge and level of understanding that is required to make the system work is greater than that of a traditional system. It is important that land managers and farmers seek advice from as many different sources as possible and learn from each other’s experiences. Truly independent advice, that is not linked to the sale of inputs, whether that be conventional pesticides or biological products, is essential.

Whilst there are many names and guises for farming systems that emphasise improving the quality of soil and natural ecosystems, regenerative farming is an empowering and farmer driven approach that combines productivity with environmental sustainability and will greatly benefit future generations.