Write about the future of farming, they said. We’d like your thoughts on the innovations that will help or hinder agriculture in the next 10 years. After I penned a sort of agricultural sci-fi column a few years ago in Farmers Guardian, I’ve clearly gained a reputation.

I actually farm in a fairly low tech way, on a thousand acres (400ha) of lowland peat and silt in the Cambridgeshire fens. Nearly all my machinery is second-hand, rented or has been on our farm longer than me. Yes, we use satellite imagery and GPS to make variable rate applications and seed plans. Yes, I’ve tried releasing sacks of predatory insects instead of insecticide. And yes, I now treat my farm-saved seed with endophytic bacteria which are meant to fix nitrogen from the air. But these are all practical steps driven by financial savings, or open-minded trials which tinker at the edges.

I don’t consider myself very futuristic. If you came to look around my muddy, and increasingly ramshackle farmyard, I think you might agree.

At the same time, I farm differently than my dear old Dad did. I took over from him unexpectedly 15 years ago, when he died from cancer. I hadn’t been a farmer. I was living and working in London as a management consultant. So I came to the business knowing nothing, willing to learn, open to any idea that could prove it might work.

Innovation is more a state of mind than a new gizmo. It’s finding out what works, what doesn’t, and how to do it better.

In the last decade and a half I’ve come to know a lot of farmers – and they’ve shown me there are as many different ways to innovate as there are to cook a potato. For some it’s all about the kit – the diesel heads. For some it’s the quality of the end product, or serving the customer. For increasing numbers it’s all about the soil and “biology”. But for all of us in the years ahead, it will be more and more about remaining economically viable.

Arable farmers are in a uniquely disadvantaged economic position. There are lots of us, and we produce huge amounts of interchangeable commodity products. Because none of us produce enough to have any bargaining power, we are each price takers. When you then consider that our costs too are increasingly outside our control it’s easy to write off the whole industry as a bad job. Except, people need to eat – and the only place that comes from is agriculture. Economically, we are plankton: feeding everything, by being fed on.

Exploitation of farmers by bigger economic fish means we in turn must exploit our own resources. This is often our own labour, or the labour of our family members. It is also our natural capital – eroding what our farms can sustainably generate by maximising inputs and cultivations for short term gains.

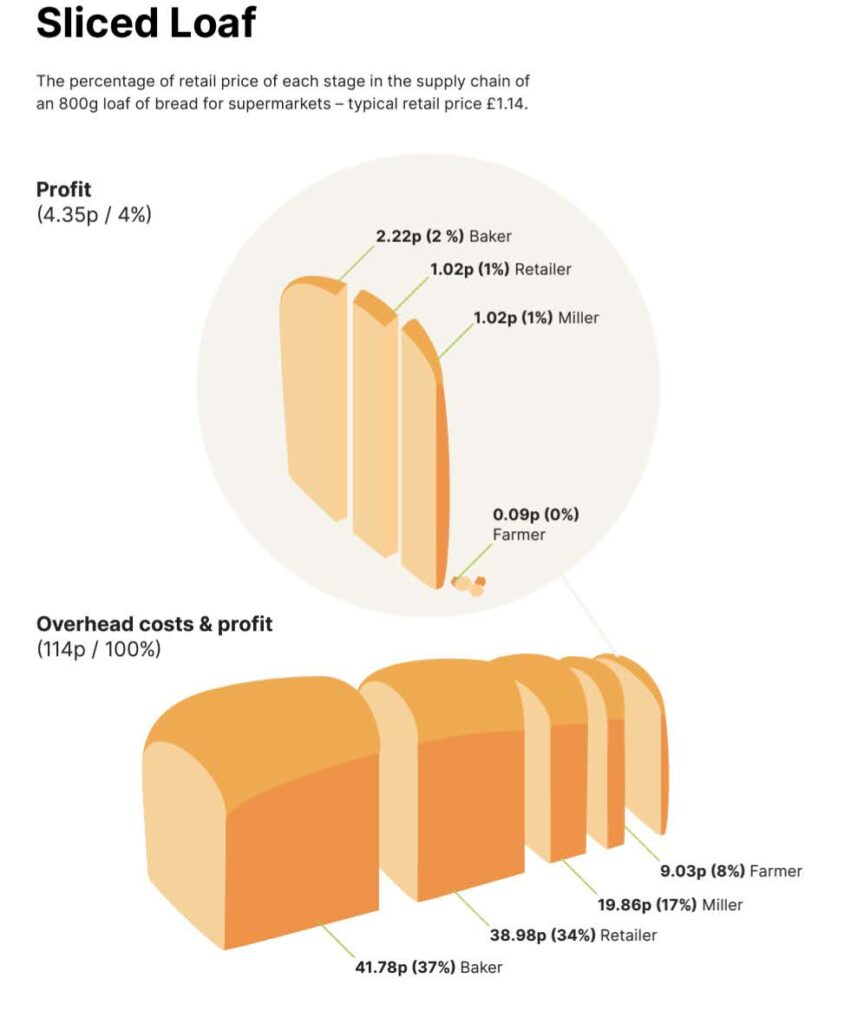

Even so, many farmers make a negative return on their capital, selling produce below the cost of production. Even when there is a return, as a proportion of the final product it’s tiny. The campaign group Sustain calculated that the whole profit on a £1.14p sliced white loaf, is 4p. The miller and the retailer each get a quarter of this. The farmer’s reward is 100 times less than that, 0.09p – if they get anything at all.

Subsidy is what used to make this mad system tick over. It allowed farmers to sell food below cost, and meet high environmental standards, without going bust. That subsidy is now nearly all gone.

Forgive me for being blunt; the future of farming in this country won’t be secured by a new widget, genetic wizardry or planting with the phases of the moon. We need a way for farmers to capture more of the value they create. Without that, our food system has no future.

I asked attendees of this year’s Oxford Farming Conference a simple poll question: “Are UK farmers in competition with each other?” – 75% of respondents said “Yes”. Well, if we are, we shouldn’t be.

Anyone reading this smugly thinking that their regen system, profitable diversifications, or multi-thousand hectare scale will see them through are still operating in a false comfort zone. Anything you can do on your own farm won’t be enough. The farm gate is no drawbridge. To influence the world beyond – where the return we make is really set – we need to change our mindsets, leave our farms and team up. We will need to create new organisations and business models that bring farmers together and pool our resources. It’s the only way we can exert any economic power. It’s also tried and tested.

Who are you paying when you buy a Limagrain seed variety? French farmers.

Any idea who owns the largest milk companies in the world? Dairy Farmers. To be precise: Kiwi, Danish, US, Dutch and Indian dairy farmers.

Do you know the name of the EU’s biggest retail bank? Credit Agricole – a French farmers’ bank. In the Netherlands too, the mighty Rabobank was started by farmers, for farmers.

In hundreds of examples from Japan to India, Brazil to Germany; when farmers collaborate they create value, and are able to capture it too. Why not here?

Already farm clusters are quietly assembling across the country; farmers who are beginning to see collaboration as the best way to access the new environmental payments.

A bigger and better beacon is the NFU Sugar Board (of which I’m an elected member). It has special legal status to negotiate the annual sugar contract on behalf of all growers. This year, we really flexed those collective muscles and, because of grower unity amid a mighty stand-off with a multinational megacorporation, were able to capture more than 25% more value from rising world markets for every sugar beet grower.

We need more collective producer organisations, ready to capture value and even take ownership of the supply chain. NFU Sugar is a one-off. Its unique position will be hard to replicate: but farmers do hard things every day.

Be in no doubt, the big fish won’t hand over value easily. The recent bust up over the Greener Farms Commitment shows the widely-held expectation that farmers are supposed to just hand it all over, and be grateful for the business.

What supply chains really need now is our data; information only we can provide about our environmental footprints. We have become so used to passing up the value of our produce, I fear too many of us think we have to hand over this new value from our data too. But this is an opportunity to draw a line in the soil. Data is a lot easier to pool than wheat, cattle, or even sugar contracts, and collectively we have a monopoly on it. Can the worm turn?

With political, market and climate instability rising around the world, farmers everywhere are protesting. Most of these demos are asking for more from governments. A few are forming political parties, perhaps to become part of governments, or to wreck them. I say, the solution to economic problems is economic action.