Written by Mackane Vogel, Assistant Editor, No Till Farmer

New technology in the world of no-till needs to be solutions-oriented in order to reach farmers in a timely manner.

No-till farming, much like agriculture as a whole, has evolved a lot over the last several decades. From new machinery and technology to scientific solutions for weed suppression, there is always something new being introduced to no-tillers. But according to Robert Saik, an agricultural technology expert, he thinks that there is one major obstacle keeping new technologies from being smoothly implemented into the agriculture industry.

“It’s called confidence,” Saik says. “The only way to get the confidence level up is to talk to people who have been there and done that. I argue that the best expert to help your farm is probably somebody you don’t know yet.”

But Saik also believes that making no-till successful in the future is not only the responsibility of the farmer. He thinks that consumers and

politicians also need to recog-nize their role.

“My main concern for the future of no-till and agriculture as a whole is the disconnection of consumers, and in particu-lar, politicians from the pragmatism of agriculture,” Saik says. One key trait that almost every farmer possesses, accord-ing to Saik, is the ability to adapt and change on the fly. Saik believes this is crucial for the success of no-till in the future.

“People make mistakes in their career, but you learn from them,” Saik says. “People seem to forget that we are pretty good at learning, unlearning and relearning in agriculture.”

Ag History

To understand where no-till is headed in decades to come, it’s important to take a look at the his-tory of notill and agriculture. According to

Saik, there are 5 main categories of agriculture’s evolution: muscle, machinery, chemistry, biotechnology and convergence. “The era of muscle was really just trading horse, oxen and human calories for food calories,” Saik says. “It was a slow, laborious process usually involv-ing the tilling of land. Then kerosene and diesel fuel came along as well as machines. We’re still in the machinery age. The machines are bigger and more advanced but that part continues on.

“Then came all of the chemistries that we used, and we start-ed to figure out how to control weeds and insects in differently. We’re still in the

chemistry age, but the chemicals we use are more precise now. And genetic engineering came after that. But today we live in an era of convergence, and you can’t separate the technologies.

And I argue that biotechnology and digital technology, machinery, remote sensing, computing power — all of it is coming together.” Saik says that because of all this convergence, it can be hard for farmers to keep up, and as a result, it can cre-ate what he calls “technology

gaps.”

“The things that our iPhones can do that we don’t use them for, the things that your tractors and combines and sprayers could do that you don’t use them for, those are some of the technology gaps,” Saik says. “We can use our imagination to make new technology

work for each individual’s needs.”

Technology as a Solution

Saik says while technology could provide solutions to reducing fertilizer costs and agriculture’s environmental footprint, there are also government regulations as well as consumer stigmas that could get in the way. “The future could be organic, but it would have to be genetically modified organic,” Saik says. “Because the only way I see us being able to reduce a lot of the pressure that we have to fight

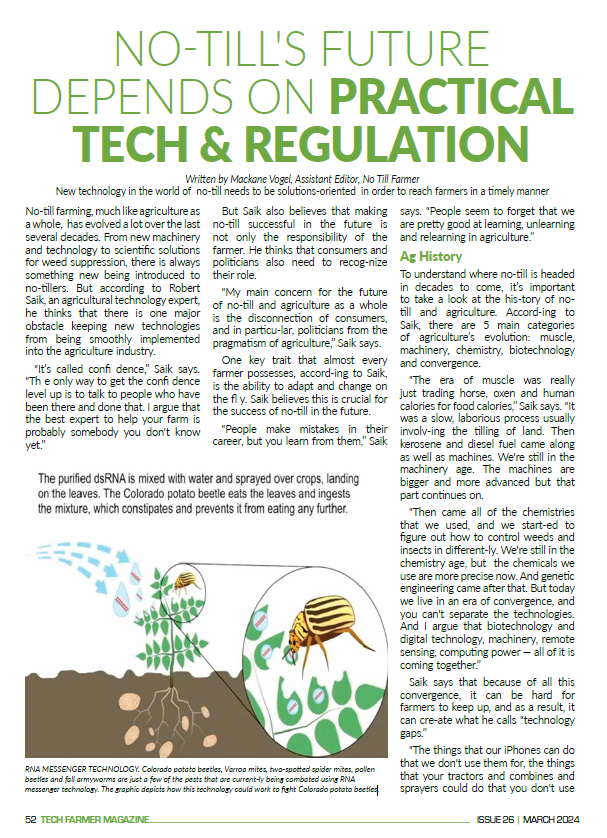

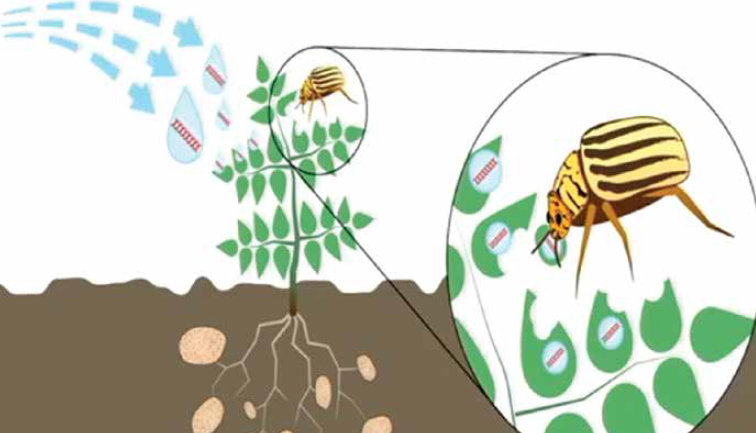

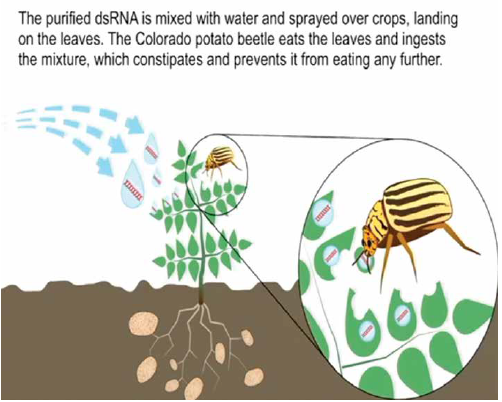

insects and diseases is genetic engineering.

beetles and fall armyworms are just a few of the pests that are current-ly being combated using RNA

messenger technology. The graphic depicts how this technology could work to fight Colorado potato beetles

Organic of the future would have to be genetically modified, or it could utilize technology. It could be geo-mechanically organic like robots

or laser beams, but either way, it’s GMO.” Specifically, RNA messenger technology is important in the world of agriculture right now. Colorado potato beetles, Fusarium, fall armyworms, these are all insects and diseases that people are working on right now using RNA technology. But Saik says it is important to make sure that the right kind of regulations are in place to allow people to start working with these kinds of compounds.

Saik says that one of his main worries is that too many pol-iticians pass policies that may look OK on paper but are unrealistic and not pragmatic in the world of a farmer. Sri Lanka is one example. The country passed a law in 2021 that essentially banned the importation of synthetic fertilizers and crop protection products.

“At that moment in time, you were able to predict the downfall of Sri Lanka because tea production fell,” Saik says. “They weren’t able to trade

tea. Foreign currency started to fall. Farmers said, ‘There’s no point in farm-ing anymore.’ They haven’t got the tools to farm.”

Consumer’s Role

Saik feels strongly that no-tillers can do a better job of embracing technology faster on the farm. “Our current adoption rate is simply too slow,” Saik says. “There’s a lot out there and not enough making it to the farm fast enough.” But to help solve this problem, Saik believes it might be beneficial to think about crops from the consumer’s stand-point. “Consumers will continue to demand convenience and transparency,” Saik says. “They want transparency so they can build trust with the people who grow their food.”

Part of the issue is that there are so many different labels on food products at the grocery store that it can be confusing and misleading for consumers. We are pretty good at learning, unlearning and relearning in agriculture…

“Maybe a sustainability index would be better on food products,” Saik says. “Maybe a consumer would be inclined to pay more money for a food with a higher sustainability index. I think this is where we need to go.”

Saik’s idea for a sustainability index on food would have a scale based on answers to questions about soil testing, use of slow-release nitrogen,

crop rota-tion, soil health focus and more.

Keeping It Simple

Much of the latest technology is meant to help give farmers detailed reports on each of their fields and how their crops are performing, but Saik thinks it’s pos-sible to give a farmer too much data. A large quantity of data can distract from the true problems in the field. Farmers and agronomists alike can be managing dozens or even multiple hundreds of fields at a time and simply want to wake up in the morning and know which field demands their atten-tion first.

“If you don’t have good agronomy and apply it to precision ag, all you’ve got is poor agronomy precisely applied,” Saik says. “Technology will tell a farmer where he has a problem and what the problem might be, but why is the problem there and how to fix it — that’s going to be the realm of the human being for a long time.”

Saik believes there needs to be a focus on the bottom line, and new technology and the world of “digital agriculture” should solve existing

problems. “Digital agriculture fits especially well into no-till,” Saik says. “Digital agriculture fits into strip-till, cover crops, all of this because it reduces your environmental footprint. It makes efficient use of labor. And I think we’re going to see more and more of that. At the end of the day, it’s about dropping profit into your pocket. That needs to be the focus.”