Written by Jeff Claydon

April 2023 Issue

Spring is the ideal time to check your soils and consider how to improve them, says Jeff Claydon, Suffolk arable farmer and inventor of the Claydon Opti-Till® direct strip seeding system.

Spring is an excellent time to focus on soil health and how to improve it, because regardless of where you are, excellence in this aspect of farming is essential to maximise crop production and financial performance. I will provide some pointers later in this article, but first let us discuss the impact of the weather over the last year.

On the Claydon farm we had just 632.4mm of rain between 1 January and 31 December 2022, in line with our long-term annual average of 629mm, surprisingly. More significantly, from the start of the year until harvest finished during the first week of August just 244mm fell, and September remained very dry. The situation changed after we finished drilling winter wheat on 11 October, with two thirds of our annual rainfall coming in the last quarter of the year.

The first few weeks of 2023 have also been quite unusual, with just 58mm of rain from 1 January until 15 February. Our 200ha of winter wheat, all LG Skyscraper, has come through the winter in excellent condition and although we have yet to apply any liquid nitrogen the crop has never looked ‘hungry’, retaining a lovely deep green colour throughout. When temperatures increase the first dose of nitrogen will go on and hopefully it will progress rapidly from there.

The Opti-Till® system has been used to establish crops on the Claydon family’s arable farm since 2002. The difficult-to-manage Hanslope series soils have constantly improved and provide ideal conditions for growing high-yielding, profitable crops. A 6m version of the new Claydon Evolution drill is seen here establishing winter wheat in October and in mid-February the crop was in great shape. Although designed as a direct drill, the scenario where maximum benefit is realised, the Claydon drill’s versatility allows it to be used in conventional and min-till establishment situations after soil consolidation.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————

Our winter oilseed rape did what it always does and died back considerably over the winter. Of the 61ha drilled about 5ha was severely affected by cabbage stem flea beetle and slugs. Exceptionally dry weather last summer forced slugs to go down deep into the soil to avoid dehydration but when the weather turned wet they surfaced to feast on the emerging crop. We applied slug pellets immediately after the first rain, but it was too late; the damage had already been done.

Some areas of oilseed rape looked patchy in February, but once warmer weather arrives and nitrogen is taken up it will make up ground.

Oilseed rape has a strong, deep taproot.

In mid-January we applied Kerb® herbicide to take out grass weeds in our oilseed rape, except on the small area which will be redrilled with spring oats. To date, there are no signs of it working and the forecast is for more frosty mornings over the next ten days, so it will be a while before the results are seen.

Ten days ago, we applied 200l/ha of Chafer Nuram 35 + S (35%N + 7SO3) and the seven days of frosty weather which followed hit the crop hard. Even though all our oilseed rape is the hybrid variety DK Excited the low temperatures have restricted its growth and I expect the crop to continue looking lacklustre. Oilseed rape has a good strong, deep taproot so once warmer weather arrives it should power away.

At the time of writing conditions are very dry and fields destined for spring sowing would be in an ideal condition for drilling but for one thing – the continuing low temperatures. In days of old, gauging when soils were warm enough to start drilling was done using what was technically termed the ‘grandpa’s bum’ test, i.e., if the soil was warm enough to sit on with a bare bum it was warm enough to drill. I’m pleased to say that things have moved on considerably since then with our weather station now providing very comprehensive and accurate readings from the comfort of the office, eliminating the need to compromise personal integrity or cause distress to passers-by.

The dry, sunny, but very cold conditions are very misleading. Last week the daytime temperature was down to minus 2°C, yet today’s high is 13°C with an overnight low of 3°C, so even though spring oats favour early drilling it’s perhaps too cold to sow the 77ha of Elsoms Lion that we have planned. The variety yielded a pleasing 6.11t/ha last season and this year’s crop will be sown from home-saved seed.

Overcoming the temptation to rush out with our new 6m Claydon Evolution drill requires great restraint. However perhaps we should try some drilling to see how the oats perform; they are tough characters, and if it were to turn dry like last season it could be a real winner. Or if we get an attack from the Beast from the East, we might be pleased that we were patient. Who knows? We sprayed off any grass weeds and volunteers in mid-November so that they didn’t get too big and we will apply another dose of glyphosate before drilling, then follow behind the drill with our Claydon Straw Harrow before rolling.

SOIL HEALTH IS A PRIORITY

Soil health should be the number one priority on any farm. Even in mid-February, all the land on the Claydon farm is travelling wonderfully well and so supportive that we are considering switching from 620 x 42 tyres to 420 x 50s on our self-propelled 36m RoGator® sprayer to keep tramlines narrow and minimise potential damage to the crop as it develops.

The extremes of weather over the last two or three years have highlighted the importance of having resilient, well-structured soils supported by an effective drainage system to take water away. However, achieving this using conventional crop establishment methods can be challenging.

In mid-February the soil in this field, which will go into spring oats, was in excellent condition and would have been ideal for drilling had air and soil temperatures been higher.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————

Conventional full cultivations and min-till systems can overwork the soil and destroy its structure, adversely impacting worm populations and activity. This reduces the soil’s ability to drain water in wet weather, leading to collapsing, slumping, and baking out, which increases moisture loss in dry conditions. This also starves the crop’s roots of essential air and nutrients, ultimately reducing yield potential and increasing the cost-per-tonne of production. The risks from flooding and soil erosion are also substantially higher.

Ploughing is expensive, both financially and environmentally. It creates the need for extra cultivation passes and increases fuel consumption. Turning the soil over releases moisture and CO2 to the atmosphere. Ploughing can deplete organic matter, mineralise nitrogen and harm soil life, while increasing the risk of wind and water erosion. The soil’s natural structure is destroyed, and it can no longer support the weight of heavy machinery, resulting in compaction and deeper wheelings, requiring more cultivations to repair the damage.

A min-till approach involving several shallower cultivations can also damage the soil’s natural structure and biology, which can lead to compaction and waterlogging. Min-till mixes weed seeds throughout the soil profile which allows them to germinate over a longer period. Drying the soil and preserving the weed seed bank is not helping to diminish the problem. Min-till can also dehydrate the soil which, combined with soil that breaks down easily into fine particles, can wash down the capillaries made by worms, blocking the flow of water through the profile into the drainage system. Green algae on the soil surface are an obvious sign of poor drainage and reflect anaerobic conditions, as do patchy crops on headlands.

Poor drainage on this headland is evident from visible wheelings.

Green algae on the surface indicate poor drainage.

Patchy crops on headlands are a further indicator of areas where drainage needs to be improved.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————

ADOPTING A DIFFERENT APPROACH

Instead of continuing the cycle of cultivations to resolve poor drainage/ soil structure it makes sense to find an alternative. The Claydon Opti-Till® System which we have used since 2002 has been transformational, eliminating the need for unnecessary, expensive cultivations while also reducing the cost and time involved in establishing crops. As we demonstrate the poor drainage effects on small areas, even with the Claydon system, it makes great sense to resolve them. With the reduction in cultivation costs/time using the system it has allowed us to direct these savings into drainage improvements. This has resulted in better yields, cleaner, more reliable crops, increased soil health, less erosion, better performance and ultimately reliable profitability. Our soil is made up of 55% silt 25%clay 20%sand, so this clay loam is not the easiest to farm, resulting in mainly cropping related to the combine harvester and the development of the Opti-Till® system.

The Claydon drill’s leading tine technology is at the heart of the Opti-Till® system. The leading tine loosens soil, but only where necessary, namely in the rooting and seeding zone, while the bands between the seeded rows are left undisturbed. The front tine loosens and aerates the soil, creating a friable tilth which provides a perfect environment for seedlings to germinate and develop strong, deep roots that tap into the moisture in the undisturbed banks of soil. The leading tine also breaks up any shallow compaction, reinstating the water and air balance in the soil, providing good drainage so that excess can get away from the rooting zone. This eliminates ponding through the later autumn and winter period.

Moisture is retained in the unmoved soil for the crop to access, while earthworm populations thrive as their burrows and old rooting pathways remain intact. The natural structure of the soil is also left undisturbed and as the capillaries remain unbroken water infiltration and rooting are unimpeded, which minimises stress on the crop throughout its life cycle, while soil biology flourishes. Claydon soils also have an increased capacity to support traffic in the field without risk of compaction.

A GOOD TIME TO TEST

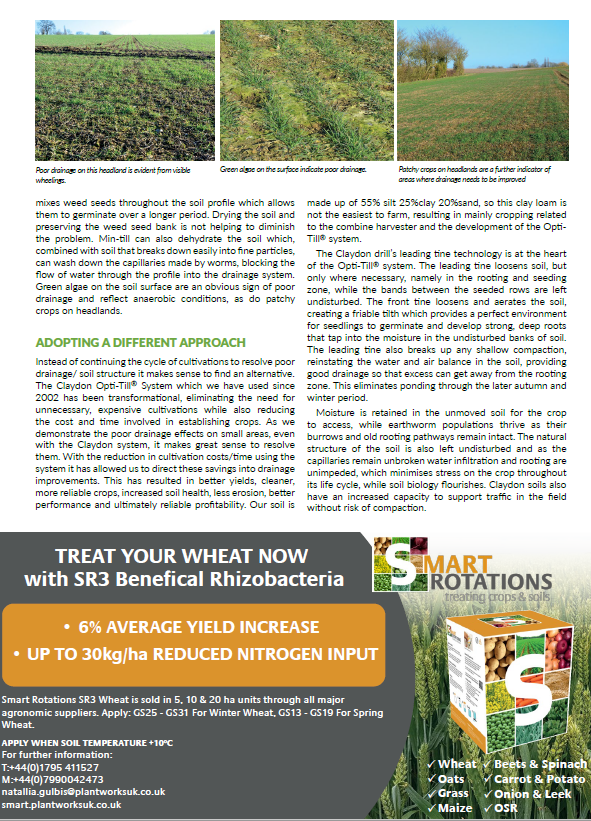

Spring is an excellent time to evaluate the condition of your soils, check for signs of compaction and ensure that drainage systems are working correctly. This is easy and cheap to do, requiring nothing more than a fork, penetrometer, water infiltration tray and a couple of glass jars. With the information they provide you can plan to correct any deficiencies.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————

Jeff Claydon takes a penetrometer reading in a field destined for spring oats.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————

The first step is to insert a penetrometer into the ground at various points across the field to check that there are no soil pans, as these will severely limit drainage and root development. They are not caused solely by compaction from heavy machinery or working when conditions are unfavourable but can result from the sedimentation of soils that have been over-cultivated and ‘settled out’ over the winter. If they are present, the probe becomes much more difficult to push into the ground and the indicator needle swings into the red.

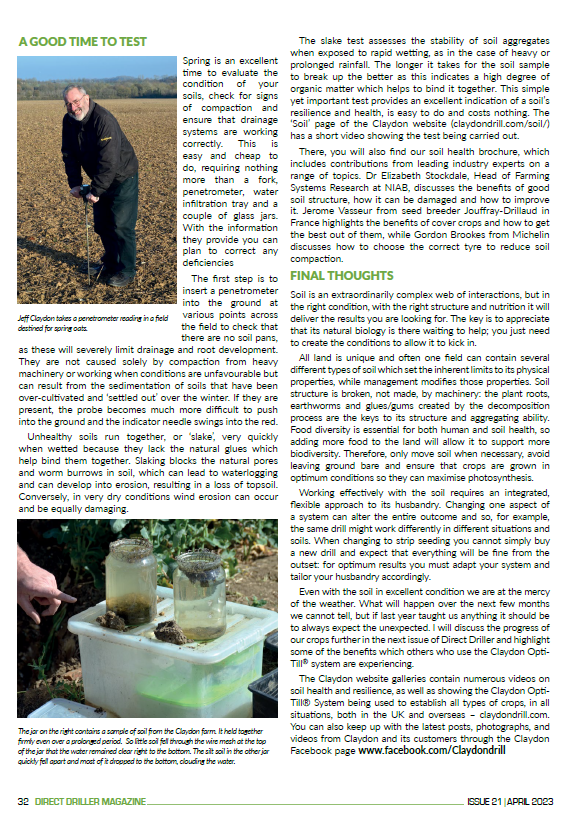

Unhealthy soils run together, or ‘slake’, very quickly when wetted because they lack the natural glues which help bind them together. Slaking blocks the natural pores and worm burrows in soil, which can lead to waterlogging and can develop into erosion, resulting in a loss of topsoil. Conversely, in very dry conditions wind erosion can occur and be equally damaging.

The slake test assesses the stability of soil aggregates when exposed to rapid wetting, as in the case of heavy or prolonged rainfall. The longer it takes for the soil sample to break up the better as this indicates a high degree of organic matter which helps to bind it together. This simple yet important test provides an excellent indication of a soil’s resilience and health, is easy to do and costs nothing. The ‘Soil’ page of the Claydon website (claydondrill.com/soil/) has a short video showing the test being carried out.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————

The jar on the right contains a sample of soil from the Claydon farm. It held together firmly even over a prolonged period. So little soil fell through the wire mesh at the top of the jar that the water remained clear right to the bottom. The silt soil in the other jar quickly fell apart and most of it dropped to the bottom, clouding the water.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————

There, you will also find our soil health brochure, which includes contributions from leading industry experts on a range of topics. Dr Elizabeth Stockdale, Head of Farming Systems Research at NIAB, discusses the benefits of good soil structure, how it can be damaged and how to improve it. Jerome Vasseur from seed breeder Jouffray-Drillaud in France highlights the benefits of cover crops and how to get the best out of them, while Gordon Brookes from Michelin discusses how to choose the correct tyre to reduce soil compaction.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Soil is an extraordinarily complex web of interactions, but in the right condition, with the right structure and nutrition it will deliver the results you are looking for. The key is to appreciate that its natural biology is there waiting to help; you just need to create the conditions to allow it to kick in.

All land is unique and often one field can contain several different types of soil which set the inherent limits to its physical properties, while management modifies those properties. Soil structure is broken, not made, by machinery: the plant roots, earthworms and glues/gums created by the decomposition process are the keys to its structure and aggregating ability. Food diversity is essential for both human and soil health, so adding more food to the land will allow it to support more biodiversity. Therefore, only move soil when necessary, avoid leaving ground bare and ensure that crops are grown in optimum conditions so they can maximise photosynthesis.

Working effectively with the soil requires an integrated, flexible approach to its husbandry. Changing one aspect of a system can alter the entire outcome and so, for example, the same drill might work differently in different situations and soils. When changing to strip seeding you cannot simply buy a new drill and expect that everything will be fine from the outset: for optimum results you must adapt your system and tailor your husbandry accordingly.

Even with the soil in excellent condition we are at the mercy of the weather. What will happen over the next few months we cannot tell, but if last year taught us anything it should be to always expect the unexpected. I will discuss the progress of our crops further in the next issue of Direct Driller and highlight some of the benefits which others who use the Claydon Opti-Till® system are experiencing.

The Claydon website galleries contain numerous videos on soil health and resilience, as well as showing the Claydon Opti-Till® System being used to establish all types of crops, in all situations, both in the UK and overseas – claydondrill.com. You can also keep up with the latest posts, photographs, and videos from Claydon and its customers through the Claydon Facebook page www.facebook.com/Claydondrill