Written by James Warne from Soil First Farming

“I don’t care what colour it is, what it looks like or it’s consistency, it’s lime, get it spread” were words quoted to me recently by an agronomist who clearly didn’t understand the basics of some simple chemistry. The above quote was part of a conversation about the quality of liming material and in particular the particle size of lime delivered to farms in the UK. I was being accused of overcomplicating liming by requesting that ‘Ground limestone’ should be specified and should be tested to make sure the product meets the specification. My point being any lime particle larger than 0.6mm (600 microns) is not going to effectively neutralise an acid pH.

This little nugget of useful information is clearly stated on the Agricultural Lime Association website (www. aglime.org.uk). For greater clarity and understanding 0.6mm is about the same size as the full stop at the end of this sentence. Not all lime is equal, and certainly our experience is that there is a lot of mis-selling going on in the ag-lime supply trade. A few years ago we were so dismayed by the quality of some of the bulk lime products being delivered to farms that we invested in a set of laboratory quality certified sieves to test our theory. To date we have tested many samples of lime and have yet to meet one which meets the statutory requirements of the Fertiliser Regulations 1991.

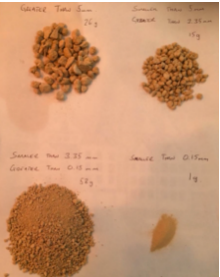

Below is one of the worst samples we found to date. To the many reading this I suspect this looks like the lime you are regularly sold, but in reality it’s total rubbish. Read on to find out why. In case you can’t read the handwritten notes in the photo, they are as follows; Top left; larger than 5mm 26% (should be zero %) Top right; smaller than 5m, larger than 3.35mm 15% (should be maximum 5%) Bottom left; smaller than 3.35mm, larger than 150 microns 58% (should be ~5%) Bottom right; smaller than 150 microns 1% (should be minimum 40%)

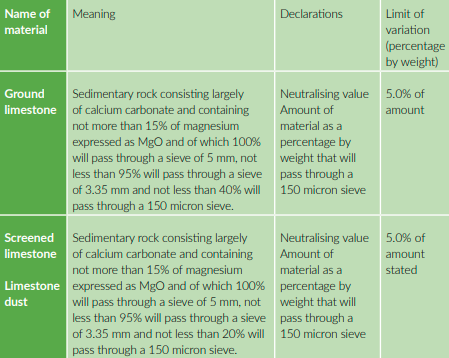

All ag-lime sold in the UK must meet the requirements of the Fertiliser Regulations 1991 to be sold as lime, for the purposes of this article I will look at limestone only, but these regulations also apply to dolomitic limestone, chalk and many other types of lime. The table below is taken from the Fertiliser Regulations. Using the detail in the table above we can see that the lime in the photo above fails on the following;

• Only 74% has passed the 5 mm sieve, where it should be 100%.

• Only 59% has passed a 3.35 mm sieve, where it should be at least 95%

• Only 1 % has passed the 150 micron sieve, where it should be at least 40% if declared ‘Ground’

Why does this matter, after all if ‘it looks like lime and smells like lime’ it must be okay surely?! My agronomist or lime supplier can’t be wrong, can they?

Sadly, yes they can and this seems to be going on around the country as far as we can tell. Why is this important? Getting soil pH and soil calcium levels at the desired levels is fundamental to all cropping, whether arable or grassland, vegetable, fruit, flower or viticulture production. Once the levels start to decline the effectiveness of inputs also starts to decline and the return on investment declines alongside. The health of the crop suffers which results in an increase in inputs which are already under pressure. You can see this becomes an ever-decreasing circle of increased cost and decreasing output.

Focus on the detail of the basics and the output and profitability will follow. In order to substantiate the claims above please read on to discover the fundamentals of why and how lime works to ensure you are spending your hard-earned cash wisely.

Neutralising value

NV is a figure given to the potential of a lime to neutralise the free hydrogen within the soil. The figure is based upon pure Calcium carbonate equivalence. A high-quality limestone will have an NV of 55. As stated above this is the potential of the product to neutralise the hydrogen ions in the soil solution which cause acidity. To give this some perspective consider the photograph below. This is oolitic Cotswold limestone as found in my garden and sold from many local quarries as a liming material.

Both the lump of rock and the ‘crushed’ pile are derived from the same piece of rock. I simply smashed a larger piece of rock with a hammer a few times to achieve the ‘crushed’ sample. Both of these samples, the lump of rock and hammer produced ‘crushed’ sample will have an identical NV. If lab tested I suspect it would have an NV of ~50. So which one is going to be more effective at neutralising acid pH soil? If the only information given to you by the lime supplier is NV, you could receive lime like that on the left, or on the right. NV is only part of the story.

So, taking the example above the ‘crushed’ sample on the right will work faster at reducing the soil pH because it has a much larger surface area and is therefore more reactive. The piece of rock on the left will do very little, if any, neutralising in a time scale that matters to you. The timescale for good neutralising is weeks to months if the lime is correctly ground, or years to decades, if larger than 0.6 mm.

Grind size

As mentioned above we now know that grind size is as important as neutralising value in determining whether the lime will actually do as intended. This is where the fertiliser Regulations 1991 become relevant because they set out the standards for lime quality as a fertiliser. If we consider these regulations for a moment it is clear that both the neutralising value and the specific material name must be given, in addition the percentage by weight passing through a 150 micron sieve must also be declared (the grind size). A limit of variation (tolerence) of 5% is allowed.

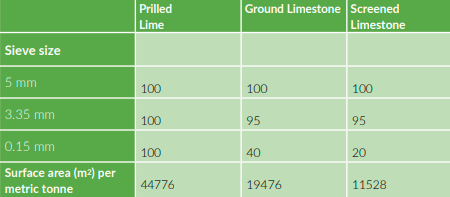

By grinding the rock finer we are increasing the surface area of the product. It is this increase in surface area which allows the lime to react faster and bring about quick reductions in soil acidity. If we calculate the degree of grinding and surface area we can see from the table below that ground limestone has a surface area nearly twice that of screened limestone, while prilled lime products can be four times the surface area of screened limstone. This increase will give greater reaction and therefore faster pH reduction.

So how fine does the rock need to be ground to be effective? The aglime website states that “coarser material requires a heavier application” and that “There is a considerable reduction in the effectiveness of liming materials containing particles above 600 microns (0.60mm, 60 mesh) unless the material is easily broken down”

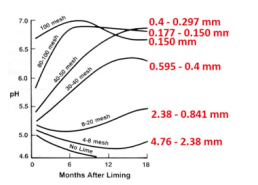

This is supported by work taken from North Carolina University in the US shown top right;

This graph clearly demonstrates that lime in the range of 0.177 – 0.150mm (177-150 micron or 80-100 mesh) gave the quickest pH rise and most sustained pH rise. The larger particle size 0.841mm and above gave a very limited pH increase and took 18 months to achieve it.

Another response I have had is “I have been using the same products for years and never found a problem”. There are two responses to this proposition;

1, you have been using a good quality product all along; or

2, soil pH testing generally occurs every 4-5 yrs in line with regular soil analysis. Suppose that your soil testing shows a pH of 5.9 and you decide to apply lime in accordance with the recommendations, this will be around 8 tonnes/ha for a medium soil (RB209). But the product you use is of low quality and does not meet the specification. This will have little effect in raising the soil pH but you don’t go back to test again for another 4 yrs. This time around the soil test is registering around pH 5.8. You are almost expecting this as we are programmed to expect the pH to be low after 4 yrs of no lime so you go through the same routine again and again. But if you had used good quality ground limestone you may find that the pH has not dropped so far and therefore less is needed.

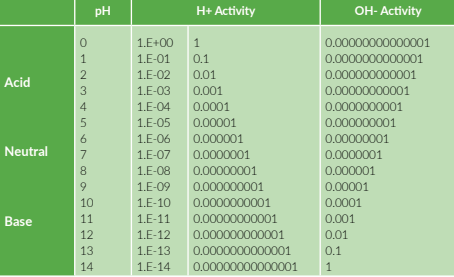

You may also find that output increases while your inputs decrease as crop health improves. But why doesn’t the pH drop lower 4 years after an application of low-quality lime? pH is a logarithmic scale which mean that each point difference in pH the hydrogen ion concentration changes ten-fold as shown in the table below. Therefore the number of hydrogen ions that need to be neutralised by the lime increases ten-fold for each unit drop in pH.

Cost comparison

If a routine application of granulated limestone extended to 200kg/ha/yr of product. Product cost is £125.00 tonne, the product cost is £25.00/ha plus a farmers spreading cost of £7.00/ ha. Total cost £32.00/ha To get an equivalent amount of useful lime from the sample shown at the beginning of this article assuming 10% fits through a 0.6mm sieve would require 2 tonnes/ha of aglime. Assuming a cost of £25.00/tonne delivered and spread. The total cost would be £50.00/ha.

The way forward

I am not saying don’t use lime, quite the contrary, lime is essential where required, but pay special attention to the quality if buying ground limestone. There is a downside to using good quality ground limestone and that is watching your neighbours benefit from your investment if your lime spreader turns up on a windy day. For the most cost-effective lime applications I suggest regular (annual or bi-annual) small applications of a granulated lime. You can apply it yourself with your own machinery, it’s 95% finely ground lime, and best of all, every penny that you spend on it will work for you.