Written by James Warne from Soil First Farming

Many years of looking at soil proves to me that cultivations never improve soil structure. They may help to overcome an immediate problem – like compaction. But they are only ever a short-term fix; and not a very good one, either.

Cultivations always leave some sort of pan. Either a mechanical pan from smearing or trafficking. Or a sedimentation pan where the act of moving the soil puts the surface crumb beneath lumps from the previous year’s pan. It may not be immediately obvious but it’s always there. And it will always build to bite you back. Subsoiling is sometimes necessary to deal with structural damage – most often from previous soil working under the wrong conditions. But rotational subsoiling as a matter of course – regardless of whether or not it’s needed or where – is nonsensical. It becomes habit, once you start doing it you need to do it more to achieve the same result. Subsoiling eventually results in a soil that packs down tighter than it was before the subsoiling took place. So it completely defeats me why so many of us who want to achieve exactly the opposite – quite often with some fairly poorly-structured soils – continually turn to metal at depth. Maybe it’s not only our soils that are addicted?

As well as hugely damaging to long-term soil structure, deep cultivation, is the enemy of organic matter. Every time we introduce air into the soil it oxidises carbon from our precious OM bank. The more air we inject the more carbon we lose. As if that’s not enough, cultivating soil decimates the worm populations. The deep burrowing worms which provide channels for drainage and air-aeration. It also disrupts the natural sub-soiling action of previous crop roots that provide preferred pathways for new root penetration & drainage for rainfall. Also not forgetting all the other important soil biology such as fungi & bacteria. Fungi, in particular, do not like being disturbed. If you are on a regenerative path and still insisting on doing some cultivation the soil biota are never going to be in a position to provide the ecosystem services you are searching for, drainage; aeration; fertility; carbon sequestration; crop health and most importantly for you, output. All of these will be compromised with the introduction of steel.

Whilst on the subject of cultivation I notice that there is a move towards light cultivation in front of spring cropping in the belief that this improves yield. The question I ask is what does the cultivation bring that increases output? Answer, it’s releasing fertility. Part of a cover crop’s function is to cycle nutrient and prevent the loss of mobile nitrogen. Unfortunately this fertility will be not be instantly released to the following crop, therefore to overcome this we need to be more considered with our fertiliser applications in the spring to ensure that we do not restrict the nutrition to the following crop. Cultivation works against everything that makes the greatest natural contribution to soil structuring – organic matter, earthworms and old root runs. And the sheer amount of horsepower, and the weight of the machine to transfer the horsepower needed doesn’t do most soils any favours either.

So, the most sustainable way of improving soil structure is less, not more, where tillage is concerned. We need to allow the sort of carbon-fuelled biology we see under permanent pastures to work its magic; not least letting the glomalin and vast array of other organic compounds produced by soil flora and fauna develop the tilth and stable soil particles we need without continual disruption and disturbance. Our preference is for cultivating only the relatively small amount of ground around the seed as part of a no-till (do not confuse with strip till) approach. This gives us the best of all possible worlds. We achieve a nice tilth where the seed really needs it for germination and establishment while maintaining the best, undisturbed soil structure everywhere else.

We get rapid and effective root proliferation to depth, just the right conditions for nutrient and water uptake and the least crop vulnerability to drought or flood. We also get ground with a greater ability to tolerate traffic, fewer weed problems, lower cultivation costs and higher establishment work rates.

Of course, this sort of natural structural improvement doesn’t offer the quick fix of sub-soiling. It can take many years of determined action to bring a soil round and overcome the problems created by over-cultivation. This is where the choice of system is of paramount importance; rotation; diversity; cover crop

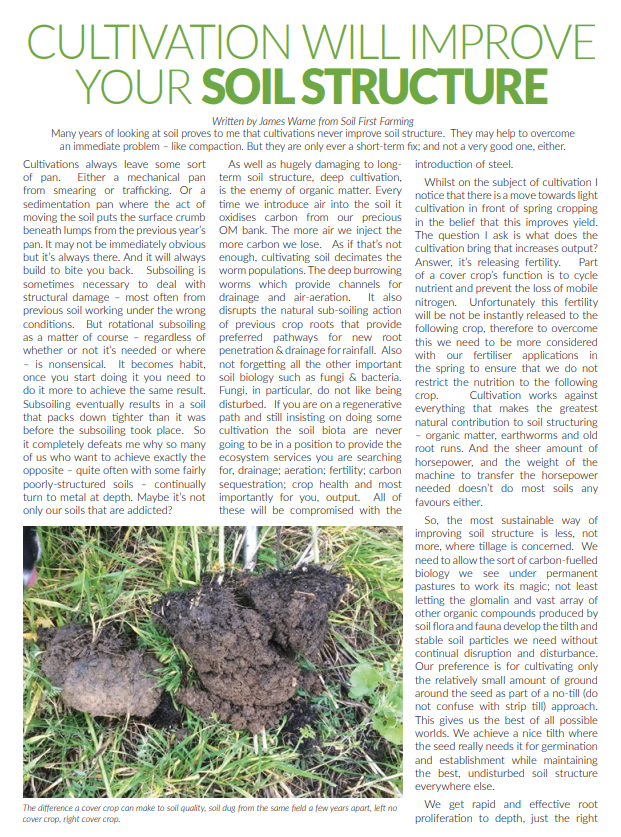

The difference a cover crop can make to soil quality, soil dug from the same field a few years apart, left no cover crop, right cover crop.

Equally, we can’t just move into direct drilling overnight and expect everything to improve. Choosing the right point in the rotation to make the switch is a useful consideration. Looking at crop performance should also give an indication of the soil functionality. While we are doing this we need to accept that we’re in a transition that may mean we have to accept some short-term pain for the long-term gain we’re after. Not only this, but we should also reconsider a number of other things we always done – like incorporating straw, grass in the rotation, muck, etc.

Appreciating the complex physical, chemical and biological characteristics of our greatest asset – the soil – and working with it to make the most of them is a better way forward than continually trying to rely on cold hard steel and plenty of horsepower. This will never give us the sustainable soil structure we need.

So, as we move towards cultivation season once again ask yourself which cultivations are really necessary? Could a cover crop do the work for you? What cover crop species could offer the best investment?