Timing Is Critical For Effective Stubble Management

Timing is everything in farming and 2018 demonstrated just what a huge difference even a few days can make when it comes to creating the ideal conditions for crop establishment, writes Jeff Claydon, who farms in Suffolk and designed the Claydon Opti-Till® System

In the last issue of Direct Driller magazine, I highlighted the importance of effective stubble management in any efficient, sustainable, profitable production system. In this edition I want to take that a stage further by outlining our findings in terms of the timing of stubble management operations, as this is critical. To maximise profitability on the Claydon farm our goal is to produce consistently high-yielding crops at the least cost per tonne. That is what I designed the Claydon Opti-Till® System to achieve and that is exactly what it delivers, providing you understand the approach and how to use it correctly.

In terms of soil structure 2018 was a vintage year. The extended period of hot, dry weather created wonderful natural, deep fissuring, while the early harvest meant that combines and associated equipment caused minimal compaction, an excellent starting point from which to establish excellent crops. After harvest the weather was ideal for an extended, highly-effective stubble management programme, with frequent light showers bringing just enough moisture so that weeds and volunteers germinated in seven to 10 days. We were able to complete four or five passes with our 15m Straw Harrow before drilling winter cereals with the 6m Hybrid drill. At the time of writing this mid-way through November all our crops look quite remarkable, very clean and full of potential.

A combined approach

A critical component of our system is to encourage weeds and volunteers to germinate quickly after harvest so that they can be taken out, between crops, using a combination of mechanical and chemical methods. Over the years we have evaluated various zero/low disturbance setups, but all our trials have shown this approach is deeply flawed here, and fraught with risks. In very dry weather the soil can bake as hard as bricks and roots cannot push through the compacted layers, while wet plastic conditions cause seeds to rot because water cannot drain away.

You need only to look down wheelings and a tramline to see the impact of compaction! Because of these fundamental shortcomings this approach makes it difficult to deliver the consistent, high yields achieved with the Claydon leading tine set-up, which creates optimal tillage and drainage in the seeding zone. To get the best from the Opti-Till system we carry out an initial pass with the Straw Harrow as soon as possible after the combine has done its job, while weeds and volunteers are at the cotyledon stage. At that point they are easy to control mechanically, but if left to develop two or more leaves the job becomes much more difficult. When carrying out post-harvest cultivations it is therefore essential to retain enough moisture in the soil to encourage rapid germination so that we can take out the cotyledons, then keep repeating that process.

On my travels around the country after harvest I saw a lot of farms wasting time, fuel, wearing metal and money on recreational tillage, using a variety of approaches. Most were simply moving too much soil, causing it to dry out and producing entirely the wrong conditions for effective stubble management. Weed seeds and volunteers were buried deep in dry soil and took much longer to germinate, so many farms were forced to delay drilling and that resulted in poor crop establishment.

The results are there for all to see in the form of patchy, uneven establishment with weeds/volunteers emerging in the growing crops, where they are much more difficult and expensive, if not impossible, to control. On the Claydon farm this autumn we used only a 15m Claydon Straw harrow to manage the stubbles followed by a 6m Hybrid drill to establish our combinable crops, with plenty of spare capacity to take on an additional 400ha contract work. It couldn’t get much simpler than that. However, to achieve optimum results requires the use of the right equipment, in the right way, at the right time.

Timing is critical

The key to effective stubble management is to appreciate the different requirements in winter and spring cropping situations, know how and when to use the Straw Harrow, then tailor operations to your own soils and conditions. It’s all about disciplining yourself to go in with the Straw Harrow even though it might seem too early because few weeds are visible. Look closely, though, and you will find countless, barely-visible cotyledons ready to emerge, and this is the very best time to take them out.

Multiple passes with the Straw Harrow will also knock out slugs and destroy their eggs, helping to create ideal conditions for drilling and crops that germinate evenly in 7 to 10 days. Within a week of finishing harvest on 24 July we straw harrowed the entire farm to distribute the chopped straw evenly and create a fine, level, 2cm-deep tilth to provide the highhumidity conditions necessary for weeds and volunteers to germinate rapidly. Straw Harrowing also halted the soil’s natural capillary action, preventing water from being drawn up to the surface and the surface from drying out, with the action of wind and sun, to form a hard, impermeable layer.

Farmers sometimes comment that we carry out more passes with the Straw Harrow than they do with a conventional establishment system, but this low-draft operation is at 20kph, covers 20+ ha/hour and uses less than 2.5 l/ha of diesel. It is fast, cheap and very effective, so we can cover the farm four times with the Straw Harrow for roughly the same cost as one application of glyphosate. This is vital to help preserve this valuable chemistry. When, eventually, we apply glyphosate it is as a single, full-strength dose prior to drilling, which maximises its effectiveness and reduces the risk of resistance.

After that initial pass, we used a range of timings with the Straw Harrow tailored to weather conditions and follow a different approach on fields which will be drilled in the autumn to those which will be spring sown. To illustrate that, I will look at three fields, ’20-acre’, ‘shop’ and ‘80-acre’, all of which have the same heavy clay soil that must be managed correctly. The former was drilled with Siskin winter wheat, while the other two are earmarked for spring oats.

From the table you can see that on ’20-acre’ we left four weeks between the fourth pass with the Straw Harrow on 3 September and the final pass on 8 October, which was five days after applying full-strength Roundup. That interval provided plenty of time for weeds and volunteers to germinate, and by Straw Harrowing just before drilling we killed any that were growing just below the surface but would have been untouched by Roundup. The crop was then drilled quickly and efficiently the following day, below the 3cm of tilth, into the preserved moisture which allowed it to get away rapidly. Due to the action of the Straw Harrow there was enough moisture in the soil for pre-emergence herbicides to work effectively.

A different approach

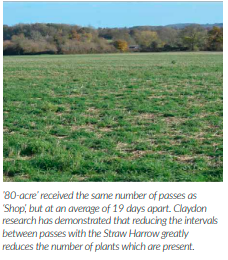

On ‘shop’ and ’80-acre’, which will be drilled in the spring, the first pass with the Straw Harrow was carried out at the same time as on ’20-acre’, but then there was a difference. The average time between passes on ‘shop’ field was 10 days, compared with an average of 19 days on ‘80-acre’. Our research highlighted that any more than two weeks between passes with the Straw Harrow allowed the plants to become much stronger and more difficult to kill. It’s clear that tightening up the intervals between passes with the Straw Harrow greatly reduces the number of plants present.

’80-acre’ has not been touched since the end of September, has greened-up nicely and shortly will be sprayed off with Roundup ahead of spring drilling. Having the chopped straw nicely mixed into the top 2cm to 3cm of soil encourages worms to proliferate and take down surface residues. The weathering action has left the soil in perfect condition for a final pass with the Straw Harrow just before drilling and having 2cm – 3cm of lovely, crumbly frost tilth on the surface will provide a perfect seedbed.

Much has been said and written about cover crops and some people swear by them. We are still evaluating their potential and have not reached any firm conclusions, but it’s very much a question of balancing their cost against the potential benefits, such as the nutrient value and soil conditions. Our approach on fields that will be spring drilled is effectively to use weeds and volunteers as the cover crop only during the autumn, taking care not to let slug numbers build up.

When we drill it is not to a set date but based entirely on soil conditions and soil temperature. We consider carefully what conditions each type of seed requires to deliver optimum performance, as the type of rooting structure it produces will affect the depth at which the front tine needs to be down and hence the set-up we use. In the spring, particularly on our clay soils, care is needed not to create plastic compaction which will press the soil particles tightly together, squeeze out any air, cause the surface to bake hard and create a layer which young plants will find difficult to penetrate, thereby stunting their development.

When drilling in the spring we will run the leading tine on the drill shallower than for autumn sowing so as not to dry the soil out, keep as much of the lovely frost tilth created over the winter on top and avoid bringing cold, wet soil to the surface where it can cause issues with establishment and reduce the effectiveness of herbicides. This is essential to ensure that crops get off to a vigorous start in warm, moist conditions, with a valuable 3cm of tilth protection. We normally drill with the front tine 10cm deep in the case of winter cereals, 15cm for oilseed rape.

RTK guidance means that the rows are evenly spaced and straight, which will allow any resistant weeds that appear between the bands to be taken out using our 6m TerraBlade inter-row hoe, which we developed to extend the range of control options that we have available and potentially reduces our use of and reliance on a dwindling number of herbicides In the next issue I will look at how we establish spring crops and look ahead to what we will be doing both in the run-up to harvest and in preparation for autumn drilling.