Written by Joe Stanley from the Allerton Project

What it is to be ‘a good farmer’ in the UK is currently undergoing a transformation of grand proportions. Many will have spent much of their careers in the belief that farmed land was for one thing only – food production – and that soil health (to the extent that it was considered at all) consisted primarily of phosphate, potash and lime indices. To be complimented on a big yield and tidy field was perhaps the greatest accolade from one’s peers.

Today, much more is being asked of farmers – and the land we farm. Food production is now on an almost equal footing with ‘natural capital services’ such as clean water and climate mitigation strategies, while farmers are navigating a new world of organic soil and carbon, nature restoration and baselining.

At the Allerton Project, we have been at the forefront of such work since we first opened our doors in 1992, and are fortunate to employ our own full time team of research scientists who carry out continuous investigation and development of nature-friendly farming techniques on our 320ha site. In recent years, much of our focus has been on soil health and productivity and how these may be able to contribute to national targets for ecosystem services and net zero.

As such, since 2017 we have been delighted to work alongside Syngenta on a long-term research project seeking to develop an understanding of a cereal cropping system based on Conservation Agriculture (CA) principles with the aim of promoting greater sustainability within the sector and making adoption of reduced intensity practices quicker and more reliable for growers and the wider industry.

CA rests on the following key, and widely appreciated, principles:

- Biological diversity (both within the rotation and the wider landscape)

- Retention of living roots in the soil through as much of the season as possible

- Maintaining soil cover to the greatest extent practical

- Reducing & optimising mechanical & chemical disturbance of the soil

This Syngenta-led pan-European project also involves NIAB in the UK and the European Conservation Agriculture Federation (ECAF) on the Continent, among other partners.

The basic concept of the trial has been to compare the economic and environmental metrics of three contrasting tillage systems across minimum 1ha plots in a five-field, five-year rotation at the Allerton Project (a heavy silty clay loam site) and across a four-field rotation at a light-land farm at Lenham in Kent. These three systems are:

- Continuous inversion tillage (with subsequent secondary tillage)

- Minimum tillage (low disturbance sub soiling / disc-based cultivation)

- Direct drilling with no additional soil movement

The planned rotation at Allerton was winter barley, OSR, wheat, spring beans (with a cover crop) and back to winter wheat. (The reality of the climate in the previous five seasons has, however, led to some ‘dynamic’ decision making on the ground!)

At Allerton, we have utilised a Dale EcoDrill across all three systems, with a Vaderstadt Carrier the prime implement in the minimum tillage system alongside a Sumo LDS where required. The ploughing was similarly worked down primarily with the Carrier, and occasionally a power harrow.

So, after five seasons, what did we discover across the rotation?

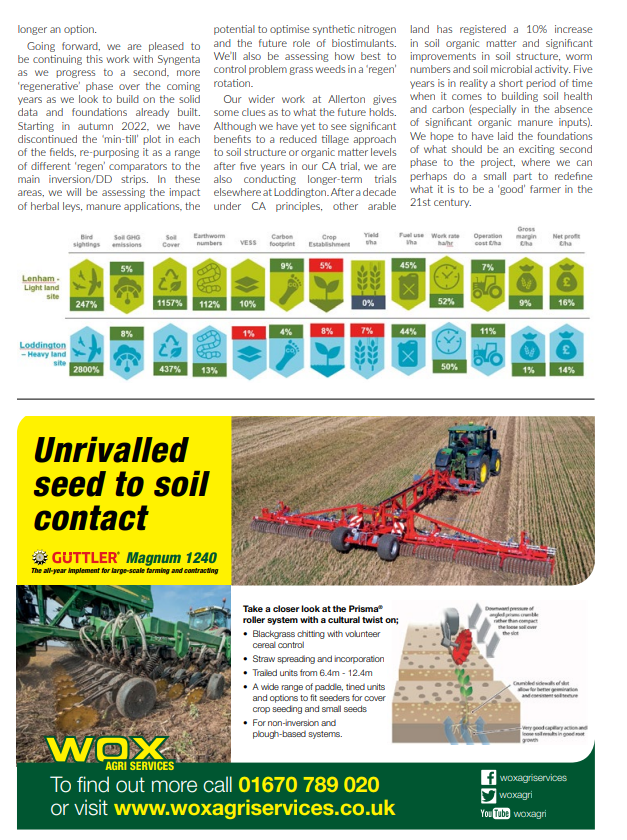

At Loddington, our crop establishment in the inversion vs DD plots has been reduced by 8%, reflected in a 7% drop in yield. However, big savings have been established in fuel use (44% down) and work rate (50% improved), while operational costs savings (11%) have been realised when reduced machinery, horsepower and depreciation requirements are taken into account. Thus, despite reduced gross output, net profitability in the DD system is 14% per hectare up on the inversion model. On the lighter land site in Kent, there has been no reduction in yield between systems, which has seen a resultant 16% increase in net profitability. The minimum cultivation regime sits solidly in the middle as a clear stepping-stone between the two.

On the environmental side, soil greenhouse gas emissions have seen an 8% reduction at Loddington (5% at Lenham) as a result of reduced soil organic matter oxidation in the DD system, while overall carbon footprint per tonne of production is down 4% (vs 9% at Lenham). In terms of soil structure, there has been a significant improvement (10%) in VESS scoring at Lenham, although we are yet to see any clear difference at Loddington on our heavy clay (following multiple very challenging years). However, our earthworm numbers are up by a respectable 13% (from an already very healthy level) whilst those at Lenham have improved by 112% over the five years, admittedly from a lower level engendered by the natural restrictions of their soil type.

Most dramatically perhaps, overwinter bird counts on the respective trial plots have demonstrated a 247% higher level of farmland bird sightings on the DD areas versus the ploughed plots at Lenham – and a 2800% increase at Loddington! To give context, numbers of foraging birds – particularly lapwing – are negligible on the ploughed ground, whilst both reduced tillage regimes seem to offer a far more attractive habitat, with spilt seed from harvest, higher invertebrate numbers, and more cover.

Thus what we can demonstrate from the first five years of our Conservation Agriculture trial is that – solely by adapting establishment technique, whilst all other inputs remain the same – significant cost savings can be accrued in both time and money, while profitability can be simultaneously increased – to the benefit of the natural environment and climate.

Clearly, from an agricultural perspective this offers multiple benefits. Increased work rates allow growers to make better use of increasingly narrow weather windows, or to cover more ground as consolidation potentially gathers pace in the coming years. It also allows for reduced size and cost of machinery in a situation where land areas remain the same. The reduced ‘carbon cost’ of operations is also one strand in what will become an element of increasing focus for farm operations, that of reducing operational emissions for farm carbon accounting to service both national net zero strategies and that of the wider supply chain – as well as, potentially, farm carbon trading. With the increasingly volatile cost of fuel, a 50% reduction in its use is also a saving worth generating in its own right.

From an environmental perspective, the potential for DD-driven systems to contribute to an enhancement in the farmed environment is clearly advantageous, again as one element of wider integration of integrated farm management across the farmed area alongside measures such as participation in agri-environment schemes. It also aligns with some of the requirements of the developing Sustainable Farming Incentive (SFI) tier of the Environmental Land Management scheme (ELM).

What we have tried to achieve with the CA trial is to put to the test much of the anecdotal evidence cited by many growers who have set out on the journey to reduced tillage over recent years. In so doing, we have collected some 80,000 data points so far which can hopefully be utilised in a way which is more compelling than abstract conceptualisation. Bar charts and data tables might not stir the soul, but they can be the basis for a hard-nosed change in business practice! As such, we certainly look forward to presenting this work at Groundswell this year on 28th June.

One point of note is that we have been conducting this work against an almost unprecedented backdrop of both financial and climatic volatility. On the challenging soils and steep slopes at Allerton, we have struggled to always establish crops in good conditions (or at all!) since 2018, with oilseed rape being a particular challenge due to the ongoing predations of cabbage stem flea beetle. The extreme market volatility arising from geopolitical upheavals in the past few years have also added an extra element of interest to the results: given the very high commodity prices available for harvest 2022 any loss of yield on the DD system was admittedly disadvantageous to the financial picture and did significantly reduce even more positive numbers achieved from the first four years. However, the financial picture must be taken over a full rotation, whilst from an environmental perspective ‘business as usual’ is no longer an option.

Going forward, we are pleased to be continuing this work with Syngenta as we progress to a second, more ‘regenerative’ phase over the coming years as we look to build on the solid data and foundations already built. Starting in autumn 2022, we have discontinued the ‘min-till’ plot in each of the fields, re-purposing it as a range of different ‘regen’ comparators to the main inversion/DD strips. In these areas, we will be assessing the impact of herbal leys, manure applications, the potential to optimise synthetic nitrogen and the future role of biostimulants. We’ll also be assessing how best to control problem grass weeds in a ‘regen’ rotation.

Our wider work at Allerton gives some clues as to what the future holds. Although we have yet to see significant benefits to a reduced tillage approach to soil structure or organic matter levels after five years in our CA trial, we are also conducting longer-term trials elsewhere at Loddington. After a decade under CA principles, other arable land has registered a 10% increase in soil organic matter and significant improvements in soil structure, worm numbers and soil microbial activity. Five years is in reality a short period of time when it comes to building soil health and carbon (especially in the absence of significant organic manure inputs). We hope to have laid the foundations of what should be an exciting second phase to the project, where we can perhaps do a small part to redefine what it is to be a ‘good’ farmer in the 21st century.