Farming mostly light soils is easy, isn’t it? I’m often told I farm “Boys’ land” and well, I guess in many ways it is. A bigger working window, low slug and blackgrass pressure all seem to make life that bit easier for me than colleagues on proper heavy clay “man’s land”. My gap year from agricultural college was spent in North Yorkshire, an absolutely stunning ring fenced farm with 100% “man’s land”. I spent most of my year ploughing up slabs of clay with the biggest, heaviest, high horsepower tractors I had ever driven. It was a dream job for a 21 year old horsepower-mad student and I promised myself that one day I would farm such land and grow the barn busting yields it was capable of.

Returning from college to my “easy” sandy loams and now with an unhealthy addiction to horsepower, it made perfect sense to set about them with similar huge tractors. Ploughing was far too slow though. The “tillage train” was very trendy, and I rapidly worked my way through the model ranges until the pinnacle of 600hp plus tractors was reached. Who needed heavy soils to justify these big and impressive monstrous machines? I wasn’t alone. The trend towards high horsepower quickly became something any self-respecting large farm must do. Marketed well by the likes of Simba and Monsanto as “eco-tillage” (although I’m not quite sure what exactly was “eco” about it all) many farms used this new method not only as a great excuse to fill their barns full of very sexy big kit but also as a way to spread existing labour over many more acres, FBT, contract farming etc… you were a nobody in farming terms if you were not shooting with Lord of the manor and his best pal land agent mates.

The FBTs got more expensive, the contracting margins slimmer as the land agents saw lower operating costs as a way to squeeze margins tighter and push up rent. It quickly became a rather pointless game to play if you wanted to actually make a living from farming and were not just in it for a couple of days shooting at the ‘big house’. However, there was a far more serious consequences to all this than lack of farmer profits. Tight rotations of wheat and rape combined with mintill and cultivator drills was the perfect breeding ground for grass weeds and pests, especially on that heavy land that I had so coveted as a student.

The more I saw others losing the battle against black grass and the plagues of slugs the more I started to see the advantage of my “boys’ land”. Trouble is, light land has one VERY big drawback ………… drought! Especially if it happened at grainfill when so often a couple of dry weeks at the wrong time will see an otherwise fantastic, clean, grass-weed-free crop go from hero to zero it less time than a pre-harvest family holiday in the Med will last. Even in a good year (read wet!) on lighter land my yield maps read like soil moisture maps, and it was this realisation a decade or so ago that set me out on my journey into no-till farming. In an epiphanous moment, whilst filling a CAT Challenger with 1000L of fuel for the second time that day, it occurred to me that a dry year in the UK was the normal in many other grain growing areas of the world. What we call a drought in the UK is a mere sunny spell in Australia. I wondered how they coped? How did they farm around this issue?

Manic research followed. The internet was a slow beast back then but eventually it became clear that the last thing any self-respecting cereal farmer in a dryland area would do is cultivate his soils. Evaporation was the enemy and cultivation and bare soil are the fastest way to lose any moisture that’s in the soil. Soil structure was the next thing I kept hearing others talk about, it made perfect sense to capture as muchof the rain that fell on the soil, reduce run off and hold the moisture in a rich sponge of organic matter for as long as possible. Apparently, worms were to become my new best friends: They along with a host of other soil organisms I had never even heard of before could apparently create this structure for me. All they asked in return was that I stopped destroying their world with cultivators and ploughs. Seemed like a fair enough deal to me and my journey as a no-till farmer began.

2018 – the year that could have been

So, a decade or so on and along comes 2018 – the year that could have been. Autumn establishment was pretty much ideal, and crops got away well. A long wet and cold winter followed, and social media started to paint a grim picture for some of the heavy land farmers. Blackgrass loves wet, heavy soil but our land was dealing with whatever mother nature threw at it just fine. The structure (well the soil life really) we have built was dealing with the rain well. Spring came and as applications went on, with the near perfect timing that lighter soils facilitate, crops got better and better.

Disease pressure was low in cool conditions, so we were able to pull back on inputs. Crop yield prediction models based on satellite radar images were forecasting yields the like of which we had never seen on this farm before and even my father (a notoriously hard man to impress) made the occasional comment that he had never seen the farm look so good. We all got terribly excited and I went away on my preharvest family summer holiday looking forward to returning to the harvest of a lifetime. I was happy with my boys’ land.

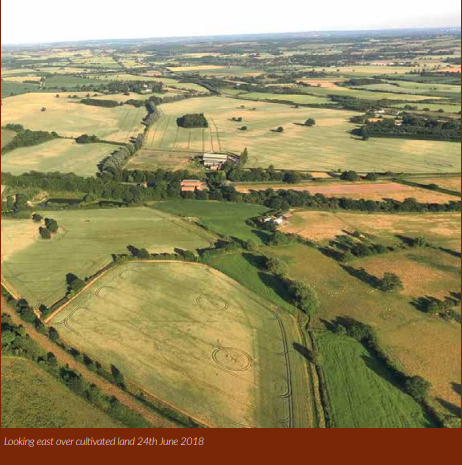

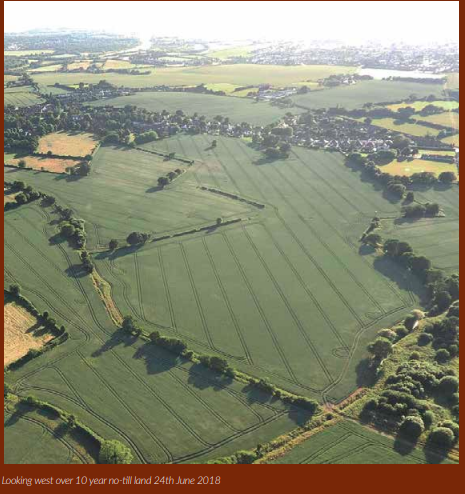

Then the inevitable happened, no rain through grainfill. The temperatures continued to rise, and the yield forecasts fell. It was visibly changing every day and the change wasn’t good. Crops were dying quickly and it’s a depressing thing for any farmer to see such potential just fade away in front of their eyes. Then whilst browsing Facebook one Sunday evening I came across a local drone photographer who had posted a few pictures taken while flying overhead that weekend.

He had been out and about taking various pictures around our area mostly to show up outlines of old building and roads in fields that the dry weather was showing up. A couple of his pictures caught my eye, they were taken from one of our boundaries and looked west over our land and then turned 180 deg east across land farmed by a couple of our neighbours. The contrast was stunning, our crops still looked pretty good, green and even however the view west over more conventionally cultivated land was very different, uneven and clearly much more affected by the drought at that point.

The deeper into no-till farming over the year I had got the more I had lost sight of why that journey had begun. Moisture was what it was all about for me and finally it seemed there was some tangible evidence that all those changes were making. Of course, there are many factors to consider here, my neighbours may have been growing different varieties, different drilling dates, different agronomy etc but the thing that was consistent is that we had all received the same amount of rain over the past month and for all of us that was nothing!

Harvest came early, in fact the earliest start ever for me here and that’s not something that bodes well as early combining means low yields as a rule. We started on the OSR and despite our lowest input spend ever on an OSR crop we were pleasantly surprised with yields slightly above our 5 year rolling average figure and interestingly very close to the numbers predicted by the satellite yield forecasting models. On to wheat and the news wasn’t so good. About half a tonne down on those rolling averages but at least milling quality was there and considering how dry it had been, the easy nature of harvest and the lack of need to dry anything it felt like a lucky escape and not too bad a result after all.

So, do I still want that “man’s land” I farmed as a student? Well “yes” is the answer. And indeed we do farm some stronger stuff for others as contract farmers. But I have come to learn that a nicely hedged position of light and heavy is probably the ideal place to be. Boys’ land and man’s land both have their pros and cons but with the correct management either can be farmed successfully under a no-till system.