Written by Harry Henderson of the AHDB, August 2018

Take a look at the European Conservation Agriculture Federation website and you’ll see Finland has the highest percentage of arable cropping in a no-till system in Europe – 13 per cent (the UK stands at 8 per cent). While you can understand dry-land countries, such as Brazil and Argentina, moving almost completely to a no-till system, why would a country where the southern tip is at the same latitude as the Shetland islands (and, presumably, a maritime climate similar to Scotland) have the greatest uptake of no-till cereal production in Europe?

It seemed the only way to find out was to stand in a field with a Finnish farmer and hear for ourselves. So in late May, bags packed, I flew to Helsinki with our strategic director Martin Grantley-Smith. First things first is day length. We landed at midnight. Although the sun had set, it was still reasonably light. By the time we got the hotel at 1am, it was already getting lighter. More on day length later… Some facts on Finland

• There were a total of 48,562 agricultural and horticultural enterprises in Finland in 2017. The number of farms dropped by approximately 1,000 on the year 2016.

• The average utilised agricultural area of the farms was 47 hectares.

• The average age of farmers on privately owned farms was 52 years.

• About 86 per cent of farms were family run farms and nine per cent were farming syndicates, less than three per cent were heirs, and less than two per cent were limited companies.

• Approximately 9 per cent of all farmers on privately owned farms are under the age of 35 and 27 per cent are over the age of 60

• Nearly 70 per cent of farms have plant production as their primary production line, and nearly 30 per cent of farms are classified as livestock farms. The rest of Finnish farms are mixed farms, with no clear primary production line

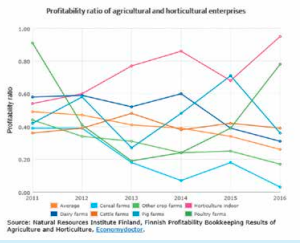

Look at the yield figures and profitability of Finnish farming and you soon get the sense that things are fairly tough. Yields, in particular, are poor.

The perception is that long summer days, 22 to 23 hours of sunlight at high summer, is good for plant growth and yield. But due to the cold, deep winters – where the sun rises at 9:30am and sets at just after 3pm, giving just under 6 hours daylight at the shortest day – the stress on the plant with the advancing spring is just too much to produce yield. For both winter and spring sown crops. This limits yield and with costs being similar or more than in the UK, income from growing cereals in Finland is hard to come by. Looking at the chart below, costs of growing a cereal crop have hovered around the 1350 to 1400 Euro per hectare mark. Divide this cost by an optimistic yield of 5.5 tons/ha of winter wheat brings a cost per ton of 255 Euros. With reducing EU support in recent years, this has made farming a financially tight business, if not a lossmaking activity.

With this, Finnish farmers have done two things. Cut costs to the bone and gone out and got a second job. A few farmers have taken on neighbouring land but an iron grip on costs still prevail, getting bigger does not mean bigger tractors for all, it means longer hours in the same tractor, double shifting with the wife in the peak time of spring.

After hearing this, it dawns on you that no-till is not a choice, it’s a necessity. Allowing compaction to creep into your soils and going out and correcting it mechanically is just not affordable. Finnish farmers had heard of the British love of recreational cultivations and smiled at us sweetly. Looking at no-till in Finland, they run a finely tuned system – all cost driven. The rotation is long, often containing winter wheat, faba beans, caraway seed, spring barley, oilseed rape and a small amount of set-a-side. Finland is, in fact, the world’s largest exporter of caraway seed, a semi-permanent crop that is combined for seed for several years and is a good addition to the gross margin.

The tractors are, for all field work, fitted with dual wheels all-round and are light high power-to-weight ratio 100hp to 140hp machines, nothing above 200hp at all. Unsurprisingly, the most common make is the home-built Valtra, built 190 miles North of Helsinki at Suolahti. The drills are also supplied domestically, either by Tume or Multiva. They are simple box drills, capable of handling seed and fertiliser and, importantly, able to work in a ploughbased seedbed or no-till. Both are discbased with attention paid to seed-depth control (essential for working in a range of conditions and soil types) supplied by rubber-tired depth wheels running close to the seeding disc. While a six-meter version is available, the vast majority are either three- or four-meter.

The thinking here is that if you limit the size of the drill, you don’t need a big tractor with a high traction requirement and so limit the chance of any compaction getting into you soils. Did I mention that compaction is absolutely avoided? Need more capacity? Have to be gettingon and not messing about with tiny drills? Get your neighbour in with their drill, set up a double shift and just get on with it! Finnish farmers were keen to get across that the hectares can be covered, if you keep the drill running. The drill was simply built to keep costs down, they doubted that air-seeders gave a justifiable improvement in seed placement and, while quite aware of precision farming, Finnish farmers just couldn’t see the cost benefit, preferring to focus on good farming practice. Having said all that, there’s a little twist. The Finnish government financially supports no-till farming.

Yup. I’ve said it now. You may well think; ‘well no wonder they are so keen’ but to be fair there is a good reason. I’ve mentioned the cold winters. After Christmas, temperatures regularly get to -20 Celsius and rarely get above freezing for two to three months. That can freeze the ground to a depth of 50cm. Permanent snow cover starts typically after Christmas in the Southwestern corner, but before mid-November in most of Lapland. The maximum snow depth is usually found around March.

Snowmelt contributes to spring floods. In the north, the peak flow of rivers always happens in spring; in the south 70 to 80 per cent of floods happen in spring. In the south, maximum flow happens in mid-April, in the north, in mid-May. And it’s this high risk in saturated fields with the huge potential of nutrient run-off, especially phosphate and topsoil loss, that leads the Finnish Government to pay farmers not to create a tilth that is more vulnerable to soil loss.

The Finnish farmer receives 30 to 40 euros per hectare each year for every field drilled, and/or left undisturbed. So. Key learnings to take home from Finland:

1. Compaction. Compaction. Learn to avoid it, rather than buy something to remove it. This is going to be tough for UK tractors adorned with ever-increasing sizes on weight boxes up front.

2. Rotation. Rotation. A long rotation and plenty of spring crops feature here. No time in the Finnish growing season for cover crops. All crop residue is left on the soil surface, as much as possible.

3. Farmer mind-set. If you expect no-till to fail, it will. The key component is the person in the tractor seat. If the attitude is not right, forget it – it’s not for you.

4. Be flexible. Finnish no-till farming is driven by economics, not fashion or religion. Most farms own a plough (they have a low resale value so it’s not worth selling) and will use it if needed. Also, if weather has delayed drilling, they are happy to use a light spring tine cultivator to open up the soil a little and drill.

5. Small machinery. Did I mention compaction? Less weight, more units, more hours in the seat (when the land demands it). So, 24-hour running is not unheard of at peak times. Time is short, summer is coming and while long days help, the season is short.