In June, Mike Abram visited three US farmers disrupting the norm in the Midwest states of Indiana and Ohio.

Driving through northern and central Indiana there are a couple of things that strike you immediately – one, how flat it is, and two, how most of the cropping is either soybeans or maize.

In a typical year, corn, as the Americans call it, is planted on 5.5m acres (2.2m ha) in Indiana, with soybeans covering a similar area, but it’s a third crop, one much more familiar to us, wheat, which is the reason why I’ve gone to meet Jason Mauck. He’s the first of three farmers I’ll visit in a near 1000-mile round-trip from Chicago covering three US states in three days.

Jason is one of a small group of US and Canadian farmers doing something out of the norm. It’s not just that he grows winter wheat – although only 410,000 acres (164,000 ha) are grown in the state – but how he does it.

Where it is grown, some growers will double-crop wheat and soybeans – planting short-season soybeans immediately following wheat harvest in July. Ag economists suggest this strategy can produce higher returns than full season soybeans or corn.

But it’s not without risk. If the weather turns hot or dry during July and August, the soybeans might not germinate, establish, set seed or grain fill. The system also takes more management – variety choice is important, and some growers don’t like the hassle of harvesting wheat in July, a key time for spraying corn or full-season soybeans.

Jason’s solution is to try to get the best of both worlds by relay cropping wheat with soybeans. The principle is the same as traditional double-cropping in that both crops are grown in the harvest year, but Jason plants his soybeans into the field with the wheat around the traditional soybean planting time in April.

He does that by planting the wheat in strips in the autumn, leaving a gap to plant the soybeans using a modified bean planter. After some trials, he’s settled on planting four rows of wheat on 7.5in spacing in 60in centres, leaving room for two rows of soybeans 20in apart. Seed rates are reduced by as much as 75% depending on whether the field is close enough to his 12,000 wean-to-finish indoor hog unit to apply manure.

The bigger gap between wheat strips encourages the crop to tiller more and grow out laterally to fill the space, Jason told me. “If you give a volunteer wheat plant space it can produce a lot of heads from a single seed, so I’m looking to exploit that to get maybe five to seven wheat heads per seed versus 1.5 heads in a mono crop scenario and create more value per seed.”

During spring the centre wheat rows typically grow taller through competition effects, while the side rows grow laterally to create a half circle crop architecture, not dissimilar to what you see in commercial lavender fields. By harvest the wheat can nearly meet across the gap above the soybeans.

“It’s all about managing sunlight and water,” he said.

Part of the value of the wheat is it removes excess soil moisture allowing Jason to plant soybeans earlier in April, with the wheat crop also creating a microclimate that protects the beans from late frosts.

In theory, that gains extra days for soybean reproductive bud set and pollination, increasing yields. The danger at planting is if it goes too dry, the wheat can remove too much moisture hurting the development of the bean.

To safely harvest the wheat without damaging the soybeans, he uses Flexxifinger pads that snap onto the combine header to compress the soybean crop below the header. Post-harvest the soybeans take advantage of the extra light and space to maximise growth.

“Historically we gain four nodes on the main stem versus narrower row mono crops, but with lots more branches, branch nodes and longer pod development on each pod site.”

At the time of my visit, wheat harvest was a couple of weeks away in his two relay-cropped fields but catching up with him after harvest one field reached 100 bu/ac (6.7 t/ha) – above the 80 bu/ac (5.4 t/ha) average for Indiana, with the other around 70 bu/ac (4.7 t/ha).

The higher yield, especially, could impact on his soybean yields – every 3-5 bushels of wheat uses around one inch of water, so growing higher yielding wheat can reduce water availability for the soybeans.

But he was hopeful the soybeans, which had grown well post wheat harvest would yield 70 bu/ac (4.7 t/ha) to provide a combined income of around $1630/ac (£530/ha) on the better yielding wheat field. With growing costs of around $250/ac (£80/ha) that would provide a gross margin of £450/ha compared with £300/ha for mono crop soy beans yielding 80 bu/ac, he says.

So is there a similar opportunity for relay cropping work in the UK, I wondered? Talking to various growers on my return my initial thoughts that it would be difficult was borne out. It might not seem obvious, but Indiana is on about the same latitude as Madrid, and that makes a huge difference in finding a crop that will mature in time after wheat harvest.

While a couple of growers have or are planning to try something similar with wheat and buckwheat or linseed, in reality the more popular bi-crop or poly-crop systems that are harvested at the same time are more likely to be successful in the UK.

The following day I was on a farm around 180 miles further east in Carroll, Ohio. This was a visit I was somewhat nervous about: I’d contacted this farmer in May to arrange a visit and had a very immediate positive response.

The farmer was David Brandt – commonly known as the “Godfather of soil health” in US regenerative farmer circles, and a man who had a viral social media meme made from his comment that farming “ain’t much, but it’s honest work”.

Those of you reading who have heard of David will probably know he sadly passed away following a road traffic accident. That was less than two weeks after I’d emailed to arrange the visit, and obviously I wasn’t sure whether his family would still be open to a visit.

But here I was meeting with David’s grandson Chris Brandt, who after working closely with David on the farm since 2017, was taking over the day-to-day running of the 400ha farm.

Chris was a joy to interview, mixing a bit of history with very clear explanations about why they were doing various practices. Like Jason the farm is a little out of the ordinary for the Midwest. David had taken over the farm in 1971, practiced no-till almost from the beginning and introduced cover crops in 1976 – a man well ahead of his time.

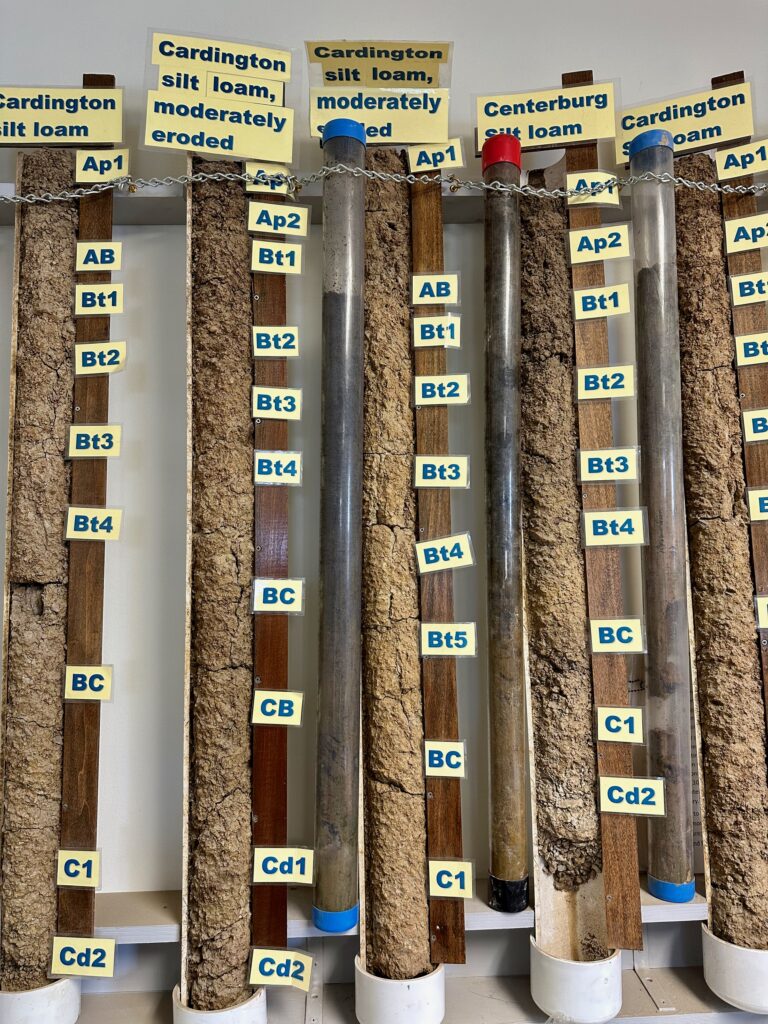

Those core soil health improving practices had helped increase soil organic matter levels from just 0.75% in 1971 to 8% on the farm, which grows 40% corn, 40% soybeans and 20% wheat. Soil samples taken in 2009 and 2022 from the same spot in some fields are proudly displayed in the farm office to highlight the improvement.

High biomass multi-species cover crops are grown after wheat ahead of the following season’s corn. High biomass multi-species cover crops grown after wheat in the rotation ahead of corn are the crops that make the difference to organic matters, Chris told me. While David had grown cover crops since 1976, it wasn’t until meeting cover crop advocate Steve Groff and North Dakotan farmer Gabe Brown in the early 2000s that he started experimenting with 6-10 species cover crop mixes.

“Fields that are now 8% organic matter were only sitting at 3-4% back then,” Chris said. “If you use monocrop covers, whether it’s buckwheat, rye, or clover you won’t see a strong increase in organic matter.”

The core components of cover crops before corn are now cereal rye, hairy vetch and crimson clover, which have two main purposes – to generate large amounts of biomass to suppress weed growth and shade the soil from the sun, and to fix nitrogen to reduce fertiliser inputs.

Added to those Chris adds species such as sunflowers, pearl millet and flax to promote mycorrhizal fungo development and increase micronutrient content in the topsoil. He’s also using some more specialised mixes with Sudan grass, oats and forage radishes and grasses, where the covers are being grazed with sheep – something which was trialled for the first-time last winter.

He reeled off some of the benefits – improvements in soil structure and water holding capacity, reducing soil erosion and nutrient loss and allowing quicker access to fields with machinery after rain and increased biological activity, including mycorrhizal fungi helping to bring nutrients to the crop and better utilisation of applied nutrients.

“Generally, in the US, it’s said one pound per acre of nitrogen in a corn field will lead to one bushel per acre of corn. What we see is that one sixth of a pound of nitrogen becomes one bushel of corn, so we’re more effective at getting those nutrients to the plant,” Chris said.

Between corn and soybeans, a simpler cover crop is grown, usually cereal rye. The later harvest of corn precluded much other than cereal species, Chris explained.

Growing a cereal rye cover crop typically generated an increase in soybean yield of 3-5 bu/ac (0.2-0.33 t/ha), while also providing an allelopathic or competition effect against mare’s tail – a difficult weed to control in soybeans.

“Soybeans require 2-4 units of nitrogen for every bushel they produce, and usually it nodulates to generate two to three of those.

“So the more nitrogen you have in the ground, the lazier the soybeans are, and they won’t nodulate as much, which reduces yield. The theory is the rye takes away nitrogen from the soil and forces the soybeans to nodulate more, increasing the base yield.”

Cereal rye was also an important part of Rick Clark’s approach, back in Indiana. Around two hours south of Chicago, Rick’s system is the most radical of the three farms – in fact probably the most radical of any farm I have set foot on, as he combines no-till and organic systems at scale.

It’s been an 18-year journey to get to this point, he explained. “I have to be careful not to paint a nice rosy picture because going organic with no tillage is extremely difficult. You need patience and a financial position that’s strong because you will have yield setbacks. I’ve experienced all of that.”

A natural storyteller – listen to his podcast FarmGreen for a taste – for 90 minutes almost without drawing breath he told me how he used to cultivate fields until they were black, until one day an unexpected rain event highlighted how that approach could cause soil erosion; how he cut fertilisers after discovering how much nutrients cereal rye cover crops held after not being able to terminate them after drilling corn; and how a researcher named Erin Silva was the inspiration in removing post-emergence herbicides in soybean by crimper-rolling cereal rye covers 45 days after drilling the beans.

But it was how he described his attitude to change that really stayed with me. “I’ve been blessed my whole life with everything,” he began. “I’ve had forefathers that understood the value of buying land. I’ve had forefathers that understood the value of building infrastructure.”

At this point I was wondering where he was going, but then he said: “And I’ve had forefathers that taught me lessons of how to think and be a thinker. It is way more important to be a thinker than it is a farmer, because you’ve got to be able to think about how to get out of situations or to create new situations.”

In telling his story, whether it was rain preventing him from spraying off a cover crop after drilling corn for six weeks or deciding to go completely organic when he was already maximising the return on investment on the farm by being 100% no-till, 100% cover crops, 100% non-GMO with a 70% reduction in inputs, it was his ability to see the potential in change that seemed a key to his success.

Driving around the farm it was possible to see both the success and some of the weaknesses of his no-till organic approach which relies on high biomass cover crops for around 70% of weed suppression and crop competition for the remainder.

In many areas weed control is good enough, but in some cereal fields, especially, some concerning areas of both chicory and thistles were evident. That’s where Rick’s ability to think through potential solutions should come into its own again.

“My first swing will be to come in with a milo grain sorghum crop after harvest if we get some rain,” he answered in response to my question about a plan.

“That should help smother the thistles out during the off season, but if we still have them next year I’ll go to alfalfa. Two years of alfalfa, cut five times a year and this will be gone,” he suggested.

So how achievable is no-till organic production in UK conditions? In talking to Rick, my impression was that understandably he, like me and US farming, wasn’t that knowledgeable about the challenges we face in the UK with grassweeds, diseases and pests and our weather, which is no doubt why he stressed than context is important when I asked about replicating his system elsewhere.

“One of the soil health principles is context. Where are you in the world? Our inherent soil here is 3.5-4% organic matter, so we have a lot of fuel in the tank. If you are in an environment that has less than 1% organic matter I doubt if you can take away all inputs and survive. So we have to understand where we are in the world and how far we can push the system. But I think anywhere in the world we could easily achieve a 30% reduction,” he suggested.

He also stressed that going the whole hog and being organic wouldn’t be for everyone. “You do not have to go organic,” he said. “You can still do non-GMO with a massive reduction in inputs, be regenerative and make a good profit on your farm.

“But I truly believe that if we want to maximise biology and maximise what the principles of soil health say, you have to take everything away. I understand not everyone can do that, and you have to be comfortable. If you’re only comfortable with a 40% reduction, then let’s figure out how to maximise your farm on 40% reduction of inputs.”

Understanding your own mentality and attitudes were also fundamental, he stressed. “Can you take one of your neighbours talking about you? I assume you have the same in England, in the gas station there’s a table off to one side. I call that the liar’s table. That’s where all the lies are talked about, and when you walk in and the table goes quiet and there’s no conversation, they are talking about you. So you have to be willing to take on that negativity because there will be a lot.”

It made me wonder on the drive back to Chicago on a very straight road, looking at field after field of corn and soybeans produced in a very conventional manner, about change and what drives it? Is fear the major reason that holds back change in the US and other parts of the world? Or is it government policy, crop insurance, big ag or something completely different?

On the face of the savings Rick claimed he was making – over $2m/year in fuel, fertiliser and pesticides – you can’t help but wonder why more in his region weren’t banging down his door asking him for advice and how he did it. Or why Jason wasn’t relay cropping across a bigger area, and why more growers weren’t double-cropping that way?

But a common thread I’ve discovered in meeting over the past few years some of the leading lights in North American regenerative agriculture from Rick Clark to Gabe Brown to Blake Vince in Canada and Chris Brandt is that their neighbours aren’t in a rush to copy them.

Is that the same here? It doesn’t feel like perhaps it is. In Norfolk, where I live, there’s a group of farmers applying regenerative approaches in north and west Norfolk, for example, or down in Kent there’s another cluster who farm not so far away from each other. There will be other similar clusters across the country I’m less familiar with.

But does that mean we are more supportive as a community through organisations such as BASE-UK, the Farming Forum’s direct drilling section and indeed this publication, or is there more to it? Or perhaps I’m wrong and on a smaller scale, we’re just like the Midwest, where those practicing regen ag seem like relatively small fish in a big pond? What do you think? I’d be interested in your thoughts – abramcommunications@gmail.com