Written by Ranald Angus

Ranald Angus NSch 2021

Before my Nuffield Farming Scholarship journey, I was fortunate enough to be given the chance to visit Argentina in 2014 on a Young Farmer’s study tour as part of a group of 15 enthusiastic young Scots. We gained a unique insight into an agricultural colossus on a “once in a lifetime” trip, which was a thoroughly enjoyable and unforgettable experience.

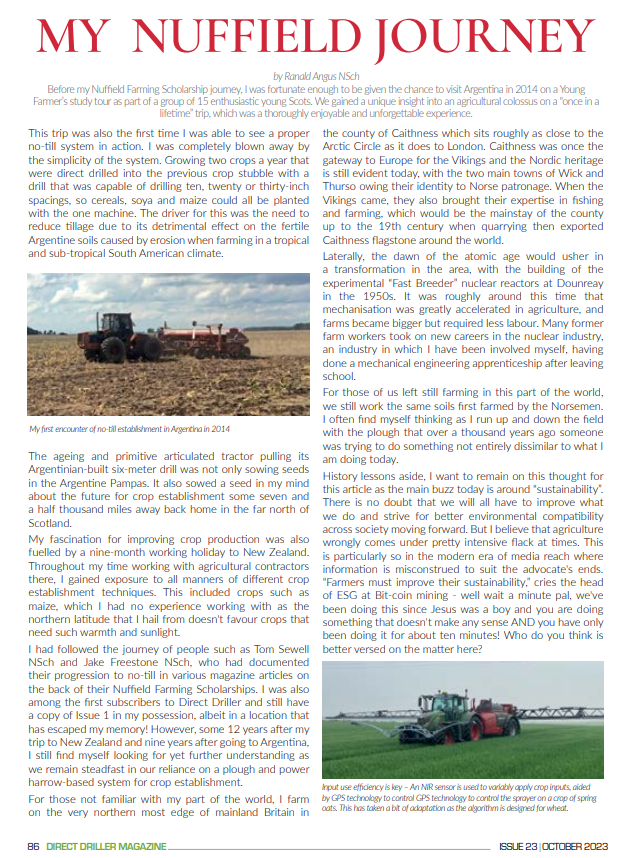

This trip was also the first time I was able to see a proper no-till system in action. I was completely blown away by the simplicity of the system. Growing two crops a year that were direct drilled into the previous crop stubble with a drill that was capable of drilling ten, twenty or thirty-inch spacings, so cereals, soya and maize could all be planted with the one machine. The driver for this was the need to reduce tillage due to its detrimental effect on the fertile Argentine soils caused by erosion when farming in a tropical and sub-tropical South American climate.

The ageing and primitive articulated tractor pulling its Argentinian-built six-meter drill was not only sowing seeds in the Argentine Pampas. It also sowed a seed in my mind about the future for crop establishment some seven and a half thousand miles away back home in the far north of Scotland.

My fascination for improving crop production was also fuelled by a nine-month working holiday to New Zealand. Throughout my time working with agricultural contractors there, I gained exposure to all manners of different crop establishment techniques. This included crops such as maize, which I had no experience working with as the northern latitude that I hail from doesn’t favour crops that need such warmth and sunlight.

I had followed the journey of people such as Tom Sewell NSch and Jake Freestone NSch, who had documented their progression to no-till in various magazine articles on the back of their Nuffield Farming Scholarships. I was also among the first subscribers to Direct Driller and still have a copy of Issue 1 in my possession, albeit in a location that has escaped my memory! However, some 12 years after my trip to New Zealand and nine years after going to Argentina, I still find myself looking for yet further understanding as we remain steadfast in our reliance on a plough and power harrow-based system for crop establishment.

For those not familiar with my part of the world, I farm on the very northern most edge of mainland Britain in the county of Caithness which sits roughly as close to the Arctic Circle as it does to London. Caithness was once the gateway to Europe for the Vikings and the Nordic heritage is still evident today, with the two main towns of Wick and Thurso owing their identity to Norse patronage. When the Vikings came, they also brought their expertise in fishing and farming, which would be the mainstay of the county up to the 19th century when quarrying then exported Caithness flagstone around the world.

Laterally, the dawn of the atomic age would usher in a transformation in the area, with the building of the experimental “Fast Breeder” nuclear reactors at Dounreay in the 1950s. It was roughly around this time that mechanisation was greatly accelerated in agriculture, and farms became bigger but required less labour. Many former farm workers took on new careers in the nuclear industry, an industry in which I have been involved myself, having done a mechanical engineering apprenticeship after leaving school.

For those of us left still farming in this part of the world, we still work the same soils first farmed by the Norsemen. I often find myself thinking as I run up and down the field with the plough that over a thousand years ago someone was trying to do something not entirely dissimilar to what I am doing today.

History lessons aside, I want to remain on this thought for this article as the main buzz today is around “sustainability”. There is no doubt that we will all have to improve what we do and strive for better environmental compatibility across society moving forward. But I believe that agriculture wrongly comes under pretty intensive flack at times. This is particularly so in the modern era of media reach where information is misconstrued to suit the advocate’s ends. “Farmers must improve their sustainability,” cries the head of ESG at Bit-coin mining – well wait a minute pal, we’ve been doing this since Jesus was a boy and you are doing something that doesn’t make any sense AND you have only been doing it for about ten minutes! Who do you think is better versed on the matter here?

The topics of sustainability and regenerative agriculture go hand in hand, after all, why would you want to sustain or maintain when you can improve? By the letter of the law in its true definition I am not a “regenerative” farmer as I pass through the fields with the plough which goes against the principles of “movement”. However, I would like to make the case that farming practices that leave the land in a measurably improved state over time must surely be the most straightforward and simple definition of what could be regarded as regenerative.

In our area, livestock farming is the prevalent form of farming, albeit with many mixed farms producing grain either for livestock feed or selling a surplus for milling or malting. However, this last decade has seen a movement away from livestock towards more arable production. Spring cropping of barley and oats has been the main practice with most of the harvest taking place in September, with the straw being baled and cleared off the fields for livestock housing in the winter months.

This far north the growing season is short, with the cool, damp maritime climate meaning moisture removal is a greater problem than moisture retention. The need to remove straw and apply muck to stubbles and the addition of some years of harvesting in very wet conditions, mean ploughing is the favoured practice. Aeration and inversion of the soil are critically important for increasing soil temperature and removing excessive soil moisture for spring drilling.

The advent of the Kverneland auto-reset leaf spring was a transformative technology in the north of Scotland as this was the first machine that could handle the stones. The Norwegian-born plough brought yet more Viking influence to our land! The heat treatment of the steel is similar to that of a sword, allowing the machine to bend and flex rather than break in the stony soils. This has transformed the land and has facilitated a rapid growth in farming. In this part of the world, not only is ploughing the dominant practice, but 95% of it is done by one brand of plough.

In the 1970s extensive drainage and liming were carried out under government grants, this drained a lot of poor-quality soils and improved the production capabilities of a lot of land. However, in the modern era, many of these drains are not adequate to meet the rising flow of groundwater that accumulates with the more extreme and variable weather that we are experiencing.

Another mechanical marvel to benefit us has been the development of the modern excavator. The shear hydraulic power of modern machines can deliver a fearsome break out force to rip through the ridges of rock to bleed the groundwater away through a large bore drainage pipe. This is encased in two-inch clean gravel from the depth of the drain right to subsoil level. As a result, wet or marshy ground which was only poor grazing ground, can be transformed by modern drainage techniques and transform a field into productive arable land.

In some cases, I have seen over 200 years of drainage fail to fix a problem. Stone drains, clay tiles and 1970s plastic coil pipes have all failed to bear fruit as they all have the same problem of being unable to reach the source of the problem lying in the hard rock below. Now though, we dig right through it with the movement of our fingertips. Whilst not as snazzy as the title of being a “Regen Farmer”, performing good agricultural land husbandry by creating drainage, applying lime, using crop rotations and conserving soil health make a significant impression when done right.

You must surely have earned the right to call yourself a “Regen Farmer” when you have not merely improved the land but moreover, you’ve completely transformed it. The mixed farming system is the original circular system, with soil health and crop yields being key indicators of the impact of what you are doing. With soil carbon content up at nine percent, there may be some room for improvement, but things are certainly not horrific at the moment.

For me, the concept of “Regen Farming” is about the ideas rather than the ideology, especially as farming requires a greater degree of flexibility than most other industries. The plough will continue to remain an important tool in the toolbox, but I am not opposed to a move away from it as it is a very slow and time-consuming job. The question will be how we can achieve this in our part of the world?

To me, the success of min-till or no-till relies heavily on successful cover crop production. This poses a question: How do you grow two crops in a part of the world where the growing season and the climate make it a struggle enough just to grow one main crop?

There has been a resurgence in winter cropping over the last few years as varieties have improved greatly and weather patterns have proven to be favourable for growing the crop. Perhaps a rotation of a spring crop followed by a winter crop followed by a cover crop could be an option. The warmer temperatures of summertime and better soil conditions would be more favourable towards some reduced tillage practice. But again, this will involve a lot of trial and error to work in our growing conditions.

The other side of the coin for “Regen Ag” comes in the form of carbon sequestration. Again, in my pursuit of knowledge, I have been following the development of this field for some time, back to the days before it was trendy or anything other than a niche idea. When I decided to pursue a Nuffield Scholarship, this was the topic that I decided I would study to discover how we can sequester, quantify, verify, and then sell this carbon.

The journey to “Net Zero” is going to be a long one and the Government has already started to renege on its commitments, notably the pushback on the ban of the sale of petrol and diesel cars from 2030 to 2035. To be honest this would have to be expected as simply throwing targets out there without any solutions as to how we achieve these goals is going to be a repeating theme as we progress. The opportunity here comes in the form of farmers being the solution to many of these problems. Be it food, fibre, energy, carbon or natural capital, the farmer will have the answers, and great gains will need to be made in time to unlock the opportunity that lies beneath our feet.

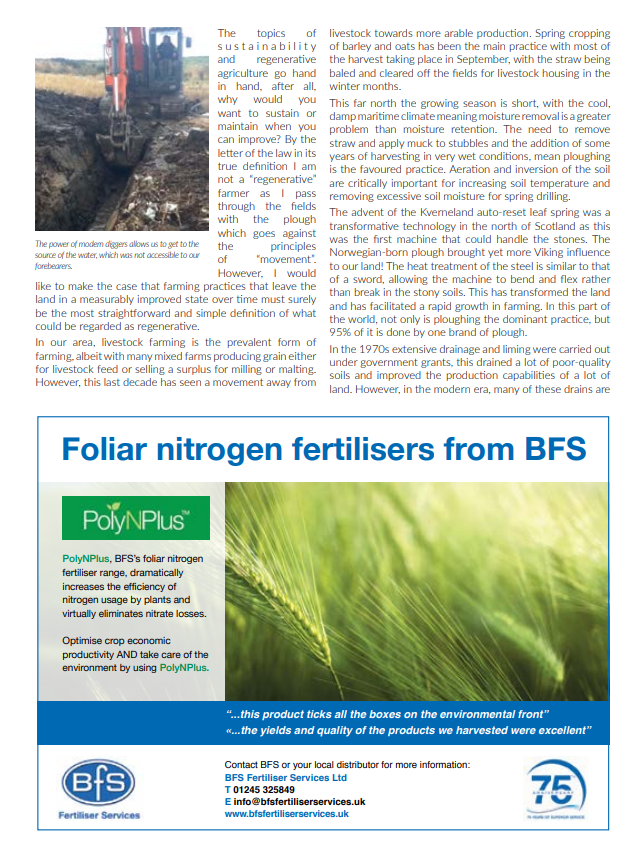

At the moment, there is a lot of emphasis on carbon sequestration, but to my mind, one area which should be the starting point is input use efficiency. The biggest source of emissions on farm comes from fuel and fertiliser. Reducing these is not always a win because if your crop yield reduces, your carbon footprint will actually increase due to your output falling. Optimising the use of inputs is an old chestnut, however whilst we always aspire to chase ‘value’ over ‘cost’, moving forward the ability to further utilise technology to help us optimise and analyse will probably see a significant uptake, particularly when input costs rise.

In time some of this technology will also help us to record and quantify our soil carbon. If we are paid to carry out regenerative practices, then this will be vital record-keeping to demonstrate that a practice has been carried out. We should also be considering the value of this data, not only to ourselves but also to third parties. Ensuring that we know how this data is being used – and who can access and use it – is important, as it could have a financial value and we could be giving away for free unknowingly.

I recently listened to a well-timed podcast just before writing this article by Andrew Dewing of Dewing Grain. Despite being a grain merchant in Norfolk which is at the complete opposite end of the country to me, I listen regularly for the market updates to get a handle on where the grain trade is at. There is often a chat about various topics or interesting people, and I am relatively familiar with Norfolk as I went there for our 2021/2022 Nuffield Contemporary Scholar Conference. Episode 253 of the Dewing Grain Podcast is worth a listen as I think it is a good discussion around regenerative farming at present.

As part of my Scholarship studies, I made my first overseas trip to Germany in the summer of last year and met many great and interesting people. The highlight of my trip was to be fortunate enough to spend a day in the company of Micheal Horsch at the Horsch company headquarters in Schwandorf.

We discussed many of the topics surrounding farming right now, and indeed some of the things I have touched on in this article including carbon, direct drilling, and input inflation as well as how the short to longer-term future for farming might look. Before the day was rounded off with a beer and a barbecue, Michael was keen to show me the information gathered from a benchmarking group of German farmers of which he is a part. There was lots and lots of data here but the key point that Michael was keen to stress was the more reliance you have on ‘digitalisation’ the lower your profit is likely to be. By secluding yourself to the office you remove yourself from the reality of what is actually happening in the field. The best farmers in this group we not only consistently the best, but they made their own judgments based on what they had seen in the field.

In this modern era, which is incredibly complicated and volatile, and now increasingly technical, there is still no substitute for boots on the ground. I had also expanded my woes over the ploughing situation with him and said to him; “Michael, what I need you to build me is a new cultivator which does the job of a plough but is not a plough!” Watch this space perhaps? Agritechinca 2023 is just around the corner…

Nearly 40 Scholars will present their findings at the 2023 Nuffield Farming ‘Super Conference’ held 14-16th November at Sandy Park in Exeter. The event also includes a pre-conference visit to nearby Wastenage Farms, and tickets are not exclusive to Nuffield Scholars – ALL are welcome and encouraged to attend. Ticketing details, and a full list of presenting Scholars can be found at the QR code or on www.nuffieldscholar.org.