Written by Andrew Voysey, Chief Impact Officer, Soil Capital

UK agriculture could benefit from payments worth as much as £500m every year if myths around carbon markets are corrected. But the industry must work harder to ensure farmers are presented with the best information about the opportunities on offer.

This was the conclusion of an industry roundtable that the agronomy firm I represent, Soil Capital, convened this Autumn with farmer, Andrew Randall, at his farm in Maidenhead. As well as farmers, the event was attended by representatives from industry bodies like the NFU, CLA, AHDB and the Association of Independent Crop Consultants, as well as land agents and all of the major distributors.

Recently published minimum requirements for Soil Carbon Codes in the UK should provide reassurance that those already using international standards are taking high integrity approaches to measuring, reporting and verifying soil carbon improvements.

But other deep-rooted beliefs, some of them based on conflicting and incomplete information, that currently hold farmers back will still persist even when clarity on standards is improved.

The event therefore focused on how to correct the most important misunderstandings about how carbon markets work so that more growers feel empowered to enter the market. Let’s review the key talking points.

Myth 1: If I trade all my carbon now, I may regret it if I need it in the future

Even degraded soil still contains carbon and many farmers believe that “carbon trading” relates to all of the stock of carbon that exists in their soil before they even enter a carbon payment scheme. Therefore, the decision can take on significant implications – as if it was about trading away mining rights – and even appear to be potentially life-changing.

In reality, carbon markets only pay for carbon added to the soil on-farm each year a farmer participates in a carbon payment scheme — not for any carbon that was already locked up in the soil many years before the farmer joined the scheme.

Myth 2: If I trade carbon, I am just giving big emitters the right to pollute

When thinking about what carbon markets do, most of us think quickly of offsetting – enabling high polluting companies to compensate for their emissions by paying others to reduce theirs.

Farmers undertaking the risk of changing their management practices to achieve such reductions can feel that this is either an unfair exchange or, frankly, an immoral one.

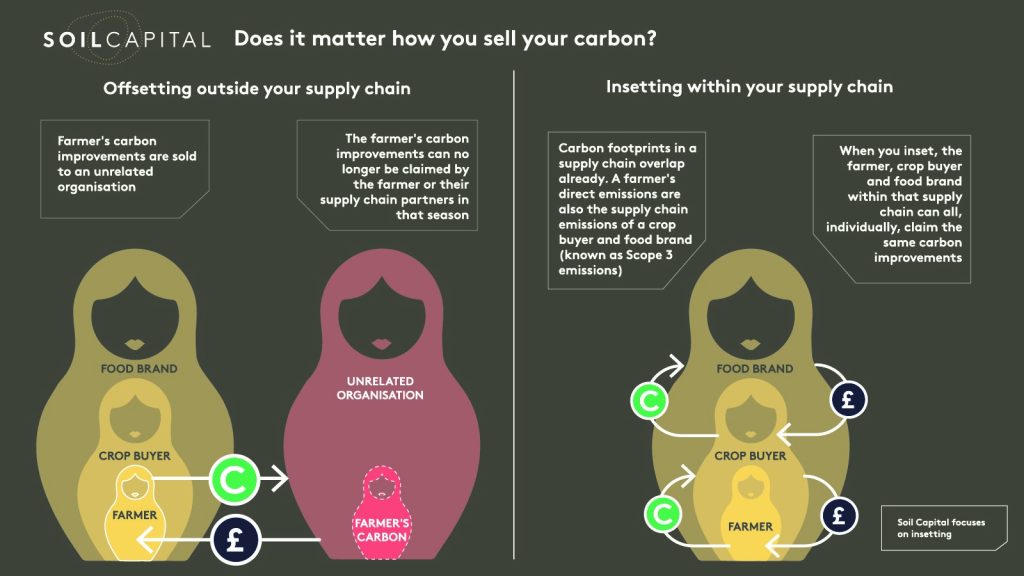

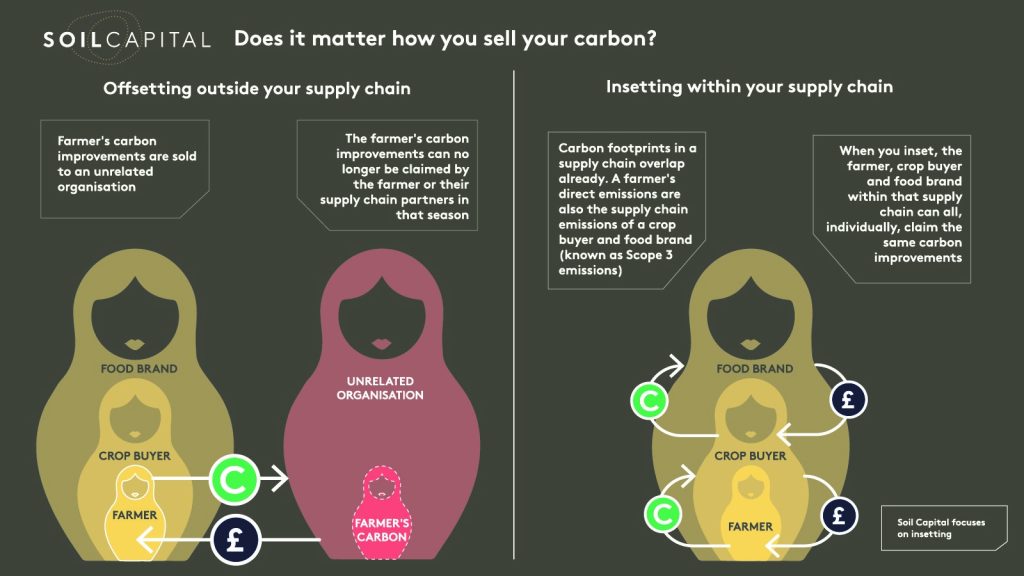

In practice, there are two quite different types of carbon trading within the carbon markets:

· Offsetting outside your supply chain – when the claim to the farmer’s carbon improvements is transferred to an unrelated organisation outside of the farmer’s own supply chain

· Insetting within your supply chain – when a company that buys the farmer’s crops also pays for the farmer’s carbon improvements, on the basis that the farmer’s carbon footprint is actually already part of the food brand’s carbon footprint by virtue of their supply chain connection

With this knowledge, farmers can see that trading carbon does not have to be about enabling big emitters to offset their emissions.

Myth 3: If I trade carbon now, I won’t be able to meet ‘net zero’ requirements in the future

Farmers are aware that the supply chain may impose net zero requirements at some point. Since many believe that offsetting is the only way to engage with carbon markets – and when an offsetting company buys the rights to the farmer’s carbon improvements, the farmer can no longer claim those carbon improvements – this can understandably make farmers nervous about making such a commitment.

But when a farmer’s carbon improvements are sold within the supply chain, as insets, those carbon improvements can be claimed by the farmer as well as the crop buyer and food brand. This is on the logic that there was already overlap between the carbon footprints of these entities before the trade happened because of the way that the carbon footprint of supply chains are constructed.

This means that, if they engage in insetting, farmers do not need to be concerned about being able to meet supply chain net zero requirements. To the contrary, by insetting, they will have benefited from payments that help them arrive at (and go beyond) this point.

Myth 4: I have to get to ‘net zero’ before I can get paid for carbon

The typical farm today emits carbon overall, but many farm systems have the potential to not only get to net zero but go beyond that and take carbon out of the atmosphere on a net basis each year. Many farmers believe that the carbon markets are only accessible once you have got to net zero.

Carbon markets have always existed, first and foremost, to reward people for reducing emissions. This is true across all industries. This is because reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the most economically efficient way has always been a firm priority in combatting climate change.

From the market’s point of view therefore, farmers do not have to already be ‘net zero’ in order to get paid for carbon. For a farm that is net emitting greenhouse gas emissions today, revenue from a carbon payment scheme can be part of a transition payment to change management practices, up to and beyond net zero.

Myth 5: Carbon prices will only rise, so it’s in my interests to wait before I value my carbon

Carbon credits tend to have higher value when they have been more recently generated through a verified scheme, since the market recognises that over time, the standards and approaches underpinning such schemes will generally improve. Generating carbon credits and then holding on to them to sell later may therefore actually not generate the best prices.

Farmer Focus

Berkshire farmer Andrew Randall, who hosted the round table on his 240ha arable farm, signed up to our certified carbon payment scheme earlier this year after researching the market and realising much of what he’d heard about carbon markets was incorrect.

He told attendees he expects to make about £50/ha in his first year by implementing practices such as direct drilling, growing multi-species cover crops, reducing nitrogen use and spreading sewage sludge.

“When people started talking about carbon payments I realised we were ticking a lot of boxes with what we wanted to do on farm and that we could capitalise on that,” he said.

“A lot of the farm-level chat has been ‘don’t sell the rights to all the carbon under your feet’, which is a huge myth that needs to be busted. I’m not selling a bank of carbon — I’m benefitting annually from the practices we do on farm, and if we don’t benefit financially from those environmental gains we’re making, it’s simply a wasted opportunity,” he added.

Mr Randall said with the combination of his planned practices, he expected to net sequester at least 2 tonnes of carbon per hectare/year.

“That will hopefully see us make over £10,000 this year, which is a useful way of starting to get back what we’re losing from the basic payment scheme,” he added.

“It has been a leap of faith in some respects, but by doing my research and getting good advice I don’t regret signing up, and I’m considering whether to bring another farm into the scheme.

Soil Capital Carbon – a proven entity

Following an external audit against the ISO standard that the scheme is certified against, Soil Capital Carbon has already disbursed its first payments to European arable farmers in June this year. Nearly €1 million was paid to 100 French and Belgian farmers on the back of practices they implemented in the previous season.

Today more than 650 farmers have enrolled overall. The programme was introduced to the UK last year, with 50 farmers having completed their first carbon assessments so far. Soil Capital targets the inset market, with the vast majority of carbon payments coming from the food and agri supply chain from agribusinesses like Cargill, AB InBev and Royal Canin (Mars Group) in support of those companies’ commitments to reduce their supply chain emissions.

These payments are the first new revenues Soil Capital has generated for farmers in Western Europe from reducing the carbon footprint of agriculture. Until now, all this has been a bit abstract. What’s more, these carbon payments are higher than the initial commitment made to farmers. Thanks to better sales prices secured with buyers, Soil Capital’s minimum guaranteed price of £23/t was raised to £27, which is a good sign. On average, farmers received £8,500 per farm in their first year. These first payments confirm the robustness and credibility of the Soil Capital programme with farmers and food companies. It is clear that farmers value the fertility and resilience benefits of improving soil health by holding more carbon in their soils. The carbon payments Soil Capital unlocks offer a meaningful incentive to farmers to undertake the difficult work of changing practices or, in some cases, maintaining those with a net positive impact. Some of the concerns in farmers’ minds are based on misunderstandings and must be corrected. Others are perfectly reasonable and need careful consideration – for which Soil Capital is happy to help.