Farm Facts:

January 2023

140Ha Home farm plus 60Ha Share farming arrangement

Arable, Beef & Sheep

Crops: Wheat, Oats, Barley, Spring Beans, Clover/Herbal leys & Permanent Pasture.

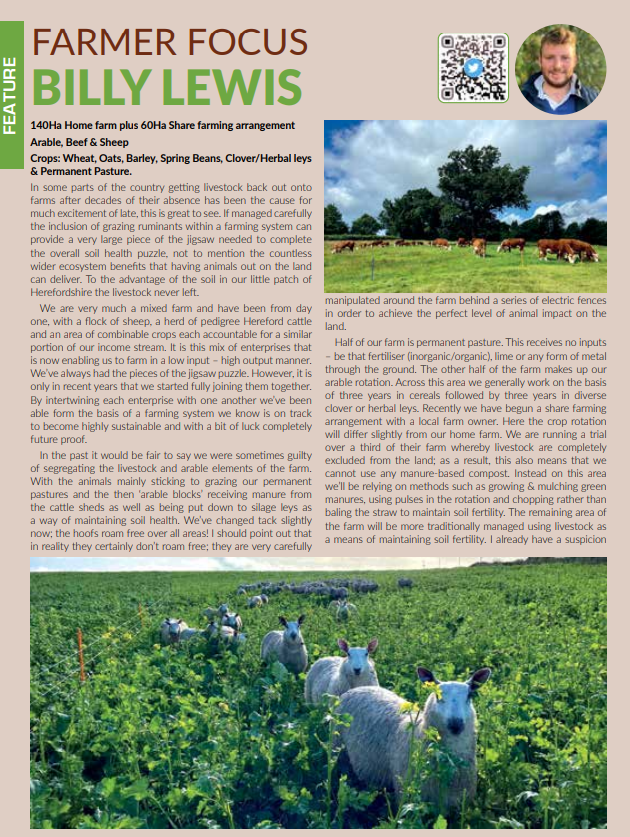

In some parts of the country getting livestock back out onto farms after decades of their absence has been the cause for much excitement of late, this is great to see. If managed carefully the inclusion of grazing ruminants within a farming system can provide a very large piece of the jigsaw needed to complete the overall soil health puzzle, not to mention the countless wider ecosystem benefits that having animals out on the land can deliver. To the advantage of the soil in our little patch of Herefordshire the livestock never left.

We are very much a mixed farm and have been from day one, with a flock of sheep, a herd of pedigree Hereford cattle and an area of combinable crops each accountable for a similar portion of our income stream. It is this mix of enterprises that is now enabling us to farm in a low input – high output manner. We’ve always had the pieces of the jigsaw puzzle. However, it is only in recent years that we started fully joining them together. By intertwining each enterprise with one another we’ve been able form the basis of a farming system we know is on track to become highly sustainable and with a bit of luck completely future proof.

In the past it would be fair to say we were sometimes guilty of segregating the livestock and arable elements of the farm. With the animals mainly sticking to grazing our permanent pastures and the then ‘arable blocks’ receiving manure from the cattle sheds as well as being put down to silage leys as a way of maintaining soil health. We’ve changed tack slightly now; the hoofs roam free over all areas! I should point out that in reality they certainly don’t roam free; they are very carefully manipulated around the farm behind a series of electric fences in order to achieve the perfect level of animal impact on the land.

Half of our farm is permanent pasture. This receives no inputs – be that fertiliser (inorganic/organic), lime or any form of metal through the ground. The other half of the farm makes up our arable rotation. Across this area we generally work on the basis of three years in cereals followed by three years in diverse clover or herbal leys. Recently we have begun a share farming arrangement with a local farm owner. Here the crop rotation will differ slightly from our home farm. We are running a trial over a third of their farm whereby livestock are completely excluded from the land; as a result, this also means that we cannot use any manure-based compost. Instead on this area we’ll be relying on methods such as growing & mulching green manures, using pulses in the rotation and chopping rather than baling the straw to maintain soil fertility. The remaining area of the farm will be more traditionally managed using livestock as a means of maintaining soil fertility. I already have a suspicion which area will perform best, but ultimately time will tell and it’s a very interesting trial to be conducting.

During the three years a field is down to a herbal ley it is grazed by our sheep and occasionally cut for silage. The beauty of grazing temporary leys is the reduction in the parasitic worm burden. In the first year following cereals it is zero, by year three when it begins to become significant the field reverts back to arable cropping and the slate is wiped clean. This approach along with tall grass grazing & long rest periods is allowing us to drastically reduce our use of anthelmintics across the farm, a small but vital piece of that ever so convoluted jigsaw puzzle. The herbal leys much like our permanent pasture also receive zero fertiliser. Instead, we are reliant upon a diverse mix of legumes coupled with long rest periods between grazing events to ensure we grow enough grass. In theory this three-year break from any artificial N is allowing the nitrogen cycle in the soil to gradually start functioning effectively again. My aim is that over the course of the next 5-10 years I’ll be able to completely eliminate the use of fertiliser over the whole farm, whilst still obtaining wheat yields in the region of 9-10T/Ha.

At peak growth during the summer ewes and lambs are on 48-hour paddock moves, kept behind electric fences at a stocking density of 300 head/acre. They enter a paddock at a cover of around 3500 kgDM/ha and come out at 2000kgDM/ha. A paddock is typically then rested for about a month before it is grazed again. A similar formula is used when grazing our cattle, who mainly stick to the permanent pasture, the difference being is that we put them into higher covers and leave more of a residual behind, as well as a longer rest period of around 50 days. These long rest periods alongside intense, fleeting animal impact are resulting in the natural seedbank in the soil bouncing back into life. Plants such as native red and white clovers, plantains, vetches, sorrel, and birds foot trefoil are becoming common place now, as well as a more diverse range of grasses – all contributing towards improving soil and animal health.

As well as grazing the grass leys we use our replacement ewe lambs to graze off winter cover crops. This year we planted 15ha to a seven way mix of Vetch, Forage Rape, Linseed, Crimson Clover, Mustard, Kale & Phacelia. Prior to planting composted FYM is spread straight behind the combine, the cover crop is then drilled in one pass with a Vaderstad Rapid with the system disc just moving the top couple of inches of soil. We plant all of our 6-8 week catch crops between winter cereals and overwinter covers by going straight into stubble with the Rapid and so far, it seems to have been a pretty bombproof establishment method.

We’ve had success in the previous two years carrying the white clover over from our temporary leys through into our first wheats to form a clover living mulch. 2022-23 is the third year we have done this and so far, so good, with wheat rowing up nicely amongst the clover once again. This is a very opportunistic method of utilising a clover living mulch, just one of the benefits of having a mixed rotation I suppose. If I couldn’t get it to work like this, I certainly wouldn’t be going out of my way to establish a special micro-clover before planting a cereal. The method is to graze the sward down before spraying off with 2.5l/ha glyphosate mixed with fulvic and citric acid. This takes the grass out but leaves the clover unharmed. We’re able to grow clover for fun on this farm so it is generally unphased by the glyphosate, however, this may well not be the case everywhere. The wheat – this year a three-way blend of Graham, Extase & Costello is then direct drilled into the clover using a John Deere 750A. Our cereal drilling is shared between the John Deere and a Weaving Sabre Tine. Last year our Costello winter wheat grown in a clover living mulch yielded 10.1T/Ha, using 60kgN/Ha and one fungicide application at T2 – the jury is out as to whether the fungicide was really needed. Interestingly just over the hedge in a more conventionally treated field (the last field on the farm to transition into a regenerative regime) growing the same variety, using more than double the N (125kgN/Ha), alongside a much more rigorous spray programme only managed a yield of 8.2T/Ha. The difference between the two: the higher yielding field followed a three year zero input herbal ley, mob grazed with sheep, the lower yielding field came out of a long stint of conventional arable cropping. The proof is in the pudding as they say.

The final piece of the jigsaw puzzle for me is how we manage our manure. A couple of years ago I was lucky enough to buy a compost turner from one of my mates. This has enabled us to transform the 500T of FYM we produce annually into a far more balanced product. The turner which is essentially a massive cork screw allows us to break up the clumps of manure and keep windrows aerobic, allowing the biology within to get to work. I tend to turn a windrow 4-6 times over a two-month period depending upon how busy I am at the time. The final result is a far superior product that is able to be utilised by the soil life a lot more effectively than raw FYM we used to spread.

I’m content we are heading in the right direction, and every little step we take compounds the efficacy of our system. What has surprised me over the past couple of years is how quickly soil health and pasture quality have been changing on the farm. Needless to say, we still have things to improve and a lot of work to do. That puzzle is still far from complete!