In the final part of our series on sap analysis, Mike Abram talks to a farming business that’s incorporated sap analysis into a wide range of cropping

Extensive sap analysis, first in trials, but increasingly in commercial practice is starting to change the way Cambs Farms Growers, part of G’s Growers, is managing its wide range of cropping.

Farming around 4000ha of land at the home farm in Cambridgeshire the business grows Little Gem and Iceberg lettuces, celery, potatoes, onions, wheat, barley and maize for anaerobic digestion.

A key target for the business is to reduce its use of inputs without sacrificing yield, says Harry Winslet, Future Farming Manager for CFG. His team conducts trials looking at how to reduce fertiliser and pesticide inputs, as well as how to implement other regenerative agriculture practices with the help of Ian Robertson from Sustainable Soil Management and RegenBen’s Ben Taylor-Davies. Successful practices are then rolled out and scaled up into commercial production.

“We are essentially an in-house research group,” says Mr Winslet.

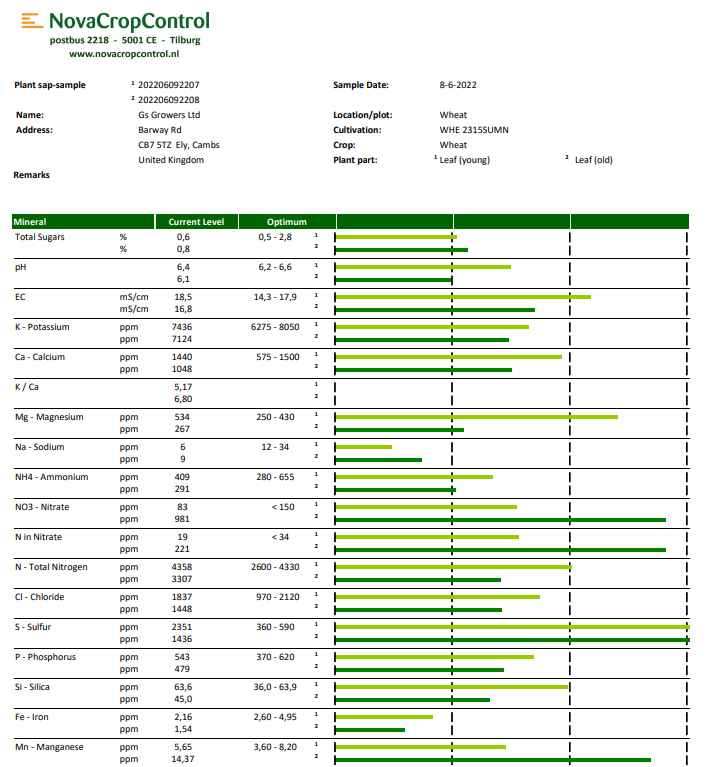

To meet that business objective of reducing inputs, Mr Winslet says he needed to better understand what was going on in the crop. That’s where sap analysis came in – starting with sending old and new leaf samples to NovaCropControl in 2019.

“What we were hoping to achieve was not necessarily the fine detail about every nutrient and every sample but understand what the broad challenges on the farm were.

“Do we have excesses in one nutrient or deficiencies consistently in another, to begin to understand what the whole farm trends were, and then to try and correlate that to crops that are growing well, tasting good with good shelf life, or to crops that are not performing well, or have pest and disease challenges,” he explains.

After four years of an extensive programme of sap analysis sampling the business has now identified nutrient markers for each of the crops that drive either good or poor performance, Mr Winslet says.

“So now when we get a sap test back, we are able to home in on those markers.”

Most growers using sap analysis will understand excessively high ammonium is a marker for likely pest attack, and high nitrate content leaves crops at risk from disease, but the research by CFG has found high potassium is a marker for poor crop performance in celery, while excessively low phosphate generally is challenging early in salad crops.

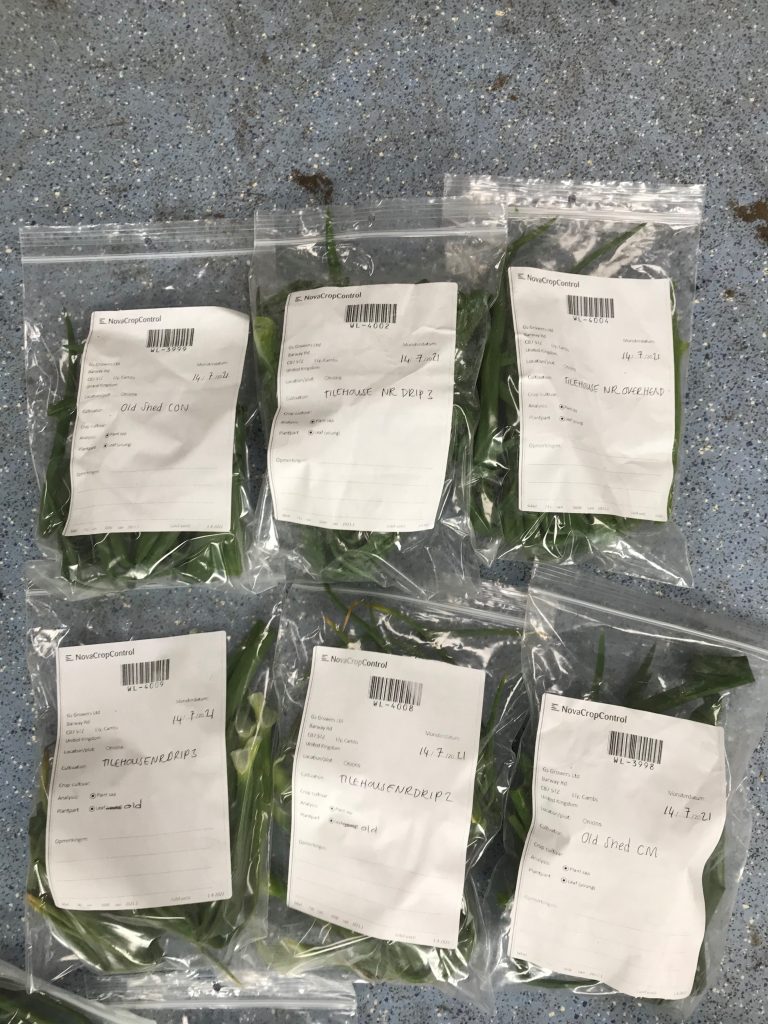

Crops are tested fortnightly typically. For lettuce and celery that means three to four times during the growing period, while wheats are measured from the autumn through to senescence. A lot of the samples are for trials purposes, but representative samples from different varieties and soil types are used in commercial crops.

“This year we took over 1000 samples for sap analysis, at a cost of around €12.50 per sample.”

That investment is paying off, Mr Winslet says. “We wholeheartedly believe in the results we are getting and the changes we are able to make off the back of them. The data we have collected over the past four season has allowed us to identify some of our challenges and make significant changes to our agronomy to try to tackle them.

“With size of the business, if we can make significant reductions in fertiliser or improvements in yield, or preferably both, the return on investment is huge.”

For example, in wheat, sap analysis is providing the evidence to make significant changes to micronutrient applications.

“Across the farm, we were consistently finding that we are probably over applying manganese and under applying others like boron, zinc and copper.”

As a result, the whole farm practice changed from applying 3kg/ha of manganese and 3kg/ha of magnesium every three weeks during the spring to tank mixtures containing copper, boron, zinc with higher rates of magnesium and lower rates of manganese. Chelators such as fulvic acid were also added to try and improve the uptake of those nutrients.

“We saw a really positive yield in our wheat crops this year. That’s not necessarily directly linked to those changes but later in the crop we saw significantly more balanced sap and tissue tests than before we made those interventions.”

Visual observations during the season on a trial area not treated with any fungicide until flag leaf suggested the crop was also free from disease, but, in a dry season, Mr Winslet says it is difficult to draw any immediate conclusions on whether the balanced nutrition was a factor.

“The hope is that we will be able to reduce our fungicide inputs.”

His team is now developing an automated Excel application that will generate a bespoke nutrient tank mix for the farm to apply from the sap analysis results and the crop’s current biomass.

The biggest challenge CFG has faced, in common with other trying to use sap analysis, is the inconsistent delivery to NovaCropControl’s laboratories in the Netherlands.

Prior to the new customs rules for exports from the UK began in January 2021, Mr Winslet says he was able to send leaf samples to NovaCropControl on a Wednesday and receive results on a Friday.

“Now there doesn’t seem to be any rhyme or reason to when parcels get to the Netherlands – we’ve had samples that get there the following day, and then others that have taken two weeks.”

That kind of delay makes trusting the data, especially around nitrogen, more difficult, he admits, which potentially could hamper some of the decision-making in key crops and the business aim to pull back on applying artificial nitrogen.

“For example, in celery we are pretty convinced that one of the issues surrounding quality and shelf life is over application of late nitrogen.

“But if you have a sample that has sat in customs for two weeks and you’re trying to interpret a total nitrogen versus nitrate reading, how sure of that result can you be?”

When the sap analysis results have been timely, the business has been using them to help improve nitrogen use efficiency in the celery crop, he says, finding it is important to have an ample supply of sulphur and magnesium in the crop, alongside a steady supply of nitrogen to build biomass.

“If we can ensure that more often than not, we find we have a very successful celery crop.

“What we are ultimately aiming to do is to reduce our nitrogen inputs based on the results of the sap analysis.”

Experience and visual observation are helping them deliver some of that nitrogen saving, but timely sap analysis results would make decision-making easier and give extra confidence, he says.

One big change the business is making is to switch from ammonium nitrate to injecting liquid urea on 80% of the celery crop.

“Moving away from ammonium nitrate is a big part of our future farming agenda. We would rather not use it because of the negative impacts on the very biology we are trying to build in our soils.

“But we didn’t want to do that at the expense of the crop having the uptake of nitrogen it needed.”

Sap analyses and biomass assessments comparing the two have shown no difference in uptake, and given the confidence to make the switch starting next season, he says. “The hope is the other salad crops will follow once we have built up the same confidence.”

Ultimately, Mr Winslet is hoping the entire group adopts the sap testing strategy on farm, both on the UK farms and their farms in other parts of the world.

“On our farm, it is initially about validating the trends we are seeing, and become better at analysing the results, and either applying or not applying nutrition as a result.

“We’ve already starting to move away from being a farm that is largely applying bulk macronutrition NPK products to one applying small amounts of micronutrition.

“The hope is we will get better at that and build the confidence to apply less and less nitrogen and phosphorus fertilisers and balance our crop health to the point we can cut pesticide use because the crops are nutritionally balanced,” he concludes.