Wilfred Mole writes about his farm.

Our family are the current custodians of 2600 acres of land with a chalk geology in Wiltshire, England. We took ownership of Lower Pertwood Farm in 2006 and resolved to establish an economically and ecologically sustainable organic enterprise.

As farmers we are observers. We observe the weather, the growth stage of crops, the condition of animals and the state of our bank accounts avidly. We have, however, failed, as an industry, to observe the obvious and the excuse that we did not recognise the effects of what we were doing does not wash. Our observations have been confined to a ‘need to know’ level; crops that need nitrogen, sheep that need worming or hedges that need trimming. We have patently failed to observe, or have refused to see, the red warning flag that has been waving at us for decades. Articles and statistics about declines in farmland birds, adverse effects of pesticides or losses of soil have been treated as the concern of academics or pressure groups.

This information has now coalesced to form a gigantic red flag that we can no longer fail to observe. It has advised us to change and there is a growing belief this change is imminent. It is important now that we begin to observe what is around us to provide proof of change. We do not always have to provide highly intellectual refereed papers in learned journals. The aptly termed observational study can gain recognition especially if it is part of a larger exercise. We have become a keen observer of all aspects of the farm environment and realise that, very often, these observations lead to positive outcomes.

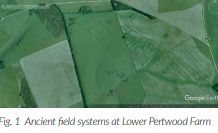

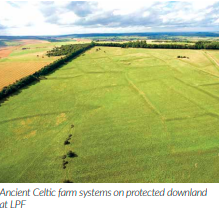

Our family are the current custodians of 2600 acres of land with a chalk geology in Wiltshire, England. This land has experienced the early efforts of the Bronze Age population, starting some 4000 years ago, to grow food for a growing population through to the zenith of the ‘chemical farming’ era of the 1970’s and 80’s. Shadows of early occupancy are prominent over a large section of the farm, overlain with modifications of Medieval origin. This land provided food, and a living, for many generations through periods of economic, political and climatic upheaval. Its soil was nurtured in order that it could maintain livestock and arable farming, whatever nature and man threw at it. Systems were developed to sustain this. In early times pare and bake, whereby thin chalky soils grew crops until the soil became exhausted, was employed.

Cropping was then abandoned and eventually livestock were grazed on reverting grasslands so that organic matter and nutrients were assimilated until cropping could begin again. A lingering memory of this practice may occur in field names Bake 1 and Bake 2. Later systems comprised rotations of grassland, fodder and arable crops as marked by field names like Sainfoin. The limits of soils suitable for cropping were well judged and were established in the name of fields, for example Starveall, which leave no doubt that this was difficult land to extract a living from. The many fields which were primarily used for grazing are memorised in having the suffix Down in the name.

Historic land management practices changed in the post-war era with the limits on soils that could be used for cropping being overcome and the necessity for livestock being reduced. Continued intensification saw inorganic fertilisers and pesticides replacing previous systems. This marked a cataclysmic landscape-scale change with the disappearance of most high quality downland, not only here but over the whole of England underlain by chalk. In addition, the character and content of the cropped area changed dramatically.

Into this changing world stepped the previous owner of Pertwood. Along with many other people a different world-view was held in which peace and love, together with everything organic, including farming, would generate happiness all around. Unfortunately for them the rest of the world did not agree and the farm, together with its entourage of alternative lifestyle people, fell on hard times. We took ownership of Lower Pertwood Farm in 2006 and resolved to establish an economically and ecologically sustainable organic enterprise. We realised that progress could be made by utilising up-to -date knowledge, technology and business acumen though this should run in tandem with tried and trusted skills and methods.

It is now over 30 years since the farm became organic and 12 since we took ownership. Those 12 years have involved a precipitous learning curve. Fortunately, we knew others gripping onto that same curve and together we have managed to maintain a forward momentum. It is gratifying that throughout this period the Organic worldwide grew steadily with the demand for our Organic Malting barley and Porridge oats expanding steadily. Prices have risen year on year and have been largely indifferent to violent global commodity price fluctuations for conventional cereals.

This is partly because the adjacent slope, of conventional farming, is rapidly becoming steeper. Perhaps it should be called the Slope of Realisation as it is coincident with an awareness that the modern agricultural revolution has come at a high price. At its most fundamental level the revolution has been paid for by the degradation of our raw material, the soil, along with numerous other ecological breakdowns which has resulted in the screws being tightened on the conventional farming business model.

The Wildlife Dividend

We have recently purchased land that has been conventionally farmed for generations and is immediately adjacent to organic system fields on Lower Pertwood Farm. This provided an opportunity to compare systems regarding an important measure of soil health, its biology. In 2018 we investigated populations of ground-dwelling invertebrates, ground beetles and spiders. Ground beetles are key indicators of change in their environment with populations that react rapidly to alterations in factors such as climate, soil cultivations, pesticide usage, cropping type etc. Levels of soil moisture have a major impact on beetle survival both directly and consequentially because of changes in the amounts of their invertebrate prey.

Prey levels depend on organisms further down the food chain, such as fungi and algae which are also affected by moisture levels. So, changes in beetle numbers reflect soil biological activity. Spiders are similarly affected by these factors. Our study certainly confirmed a difference in soil health between systems. Almost 4000 specimens were trapped, counted and identified between April and July. The organic field had three and a half times the number of beetles and twice the number of spiders than found in the conventional field.

Part of the reason for this large difference was thought to be the very dry summer weather experienced in 2018. The organic matter content of soil in the organic field was double that of the conventional field and this, together with shading provided by cover crops and weeds, aided beetle survival. Obviously any direct or longer-term chronic effects of pesticides were absent in the organic field. This exercise provided an accurate and meaningful measure of soil health. Our organic soils were more resilient to major droughting episodes and, therefore, remain more suitable for crop growth. This is an important finding if climate change predictions continue to be proved correct. These results also link into more favourable conditions for organisms further up the food chain.

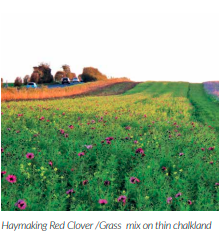

Intensive bird surveys have been conducted at the farm over the past four years with a particular focus on one typical, and now highly threatened, farmland bird. Corn bunting populations declined by 90% between 1970 and 2010 nationally and this decrease continues but diligent observations coupled with some farm management options being taken in favour of the birds has resulted in an amazing story of recovery at Lower Pertwood Farm. These birds breed in cereals and grassland then overwinter on stubble and grazed grassland. The extended provision of cereal stubbles, to help weed management, together with highly favoured leys with red clover on the farm saw an increase from 300 to 600 overwintering birds on the farm over the period 2014/15 to 2017/18. Seeds on the soil surface in stubbles and the tops of new growth in the clover/ryegrass leys provided a valuable winter food resource that enabled the winter survival of these birds.

Surveys of breeding birds, carried out in 2015 and again in 2018, recorded an increase from 132 to 235 territories, a remarkable upturn of 87% in three years. This success was promoted by the slightly later harvesting of cereal crops in the organic system compared with the increasingly earlier harvesting dates on conventional where nests are destroyed before chicks have fledged. When birds nest in grass leys cutting for silage normally takes place a week or two before fledging and, again, nests are destroyed. At Pertwood observations have determined that there is a preference for nesting in leys with red clover so those leys with white clover are cut first with red clover leys being left until chicks are observed flying. Corn bunting, along with many other farmland birds, feed their young on invertebrates and it is likely that the enhanced levels of invertebrates found in our organically farmed habitats are highly beneficial to these bird populations.

At the top of the food chain sit the birds of prey and we monitor their breeding success using nest boxes. In 2018 three broods of barn owl produced 8 young and one brood of kestrel produced five young. Interestingly, the success rate at Lower Pertwood Farm appear to have exceeded that in the surrounding locality where dry conditions have been cited as the cause of a decline. This, perhaps, again indicates that healthier, moister soils continued to supply small mammal and invertebrate food for these species on the farm whereas birds nesting on non-organic areas at other sites may have found insufficient prey to rear young.

We consider that gathering scientific evidence from the natural world to confirm that our measures are producing beneficial outcomes is crucial. We can, for a change, believe this evidence as wildlife does not have a profit motive and it does not tell lies.

The Community Dividend

Agriculture has had a bad press with farmers being judged as abusers rather than guardians of the land. Maybe some criticism is justified. Easily visible abuses, such as catastrophic episodes of hedge removal, are now being joined by major concerns regarding the state of our soils. It seems that very little that is agreeable or pleasant is seen by anyone peering over the farm gate. There is a growing perception that we are operating food factories isolated from and independent of the natural world. The path that the industry is following allows for less and less contradiction of that view. Farming must in future, operate as part of the wider ecosystem.

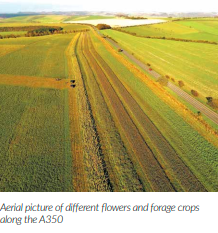

To break the bond between farming and the natural world will, logically, remove farmers from the equation to be replaced by a food production operative. For those of us following a different path it is important that we display our differences and benefits to a public who have no contact with, or knowledge of, agriculture. We have been taken aback by the reactions to a relatively straightforward and simple exercise to introduce late-summer nectar sources for invertebrates utilising colourful plants. The origins of this success lie in the use of a non-native plant, Cosmos. It grew successfully on thin, poor soils so we decided to sow a mile long strip at the edge of fields bordering the busy A350 trunk road. We added phacelia and sunflowers in one area and a field growing Sainfoin provided a colourful backdrop.

The response from the public was phenomenal with numerous congratulatory and enquiring e-mails. Observations of cars parked enabling occupants a better view of the display were frequent and instances when passers-by asked for a quick tour occurred regularly. This overwhelmingly positive reaction will be developed to educate people about organic farming. We are sure the insects would also have joined in the congratulations if they had access to bee-tea internet.com.

The Aspirational Dividend

One of the major features of Lower Pertwood Farm is its complexity. It is a kaleidoscope of land-use types ranging from large areas of gorse once use to shelter foxes and supply sport for the hunt to mature scrub ‘woodland’ which still hides Permaculture roundhouses to planted woodland, to ancient and improved grasslands to areas designated for wildlife to land on which crops are grown. Underlying this current matrix is the older one mentioned at the start of this article. Most remnants of this older matrix were significantly altered by conventional farming in the latter half of the 20th century. However, one or two fragments escaped. These occur in steep sided coombes too dangerous for tractors. The botany on parts of these coombes remains characteristic of the original, high quality chalk downland that once occupied a large portion of this site.

One of 2019s major aims will be to discover if any relict invertebrate populations have survived. This habitat type is one of the most biologically rich and diverse UK habitats and that its area declined dramatically from the mid-1960s. These remnants are potentially of great significance. To protect, enhance and, possibly, expand them would be important at a regional level. It only remains to see whether the authorities can create a regulatory environment which encourages Farmers to think more deeply about the legacy that they are leaving their children. The signs are good that this young generation have already sensed the urgent need for change.