Written by Dr Nicola Cannon, Associate Professor of Agriculture

Introduction

Herbicide resistance has become a major challenge to UK arable production and is forcing farms to rethink cropping choices and in some cases is even leading to fallowing instead of cropping to try and regain control of challenging weeds. The problem of herbicide resistance has been exasperated in recent years by narrow crop rotations, withdrawal of previously approved herbicides and a period of earlier drilling dates to try and maximise crop yield. A study by ADAS published in 2019 found that the majority of farmers view herbicides as the key method for weed control in cropping systems and that these products are often being applied in a reactive manner when weed germination is observed. There has been a shift to using herbicides in a more proactive manner but even when pre-emergence herbicides are applied there is often a requirement for some later weed control in the growing season.

Initial weed control options

The first step to regaining weed control without relying on herbicides is to develop a diverse crop rotation which allows for different sowing dates and the inclusion of crops which can be more competitive against weeds. The grower should have an understanding of the weed seed bank and therefore the weeds which are anticipated to grow in the selected crops. A detailed understanding needs to be gained of the germination periods, weed competitiveness, growth habit, flowering dates and periods of seed set and seed shedding. Varieties can selected which are known to be better at competing against weeds and then be planted to avoid the weed germination period of the key weed challenges.

The crop must be able to grow and thrive to outcompete weeds and therefore it is important to manage other obstacles to crop growth during the cropping season including the impact of soil compaction, crop diseases and pest damage. Once all of these factors have been evaluated and managed then other forms of weed control can be considered to help improve weed control.

Non-chemical weed control

Currently the main options for non-chemical weed control in a crop rely on mechanical weed control. However, improvements in precision applications may transform weed control techniques and allow improved weed species detection within the crop and enable plants to be removed by robots using techniques such as lasers, microwaves or air blasts. Currently in field scale agriculture there are three main choices of systems that can be adopted to mechanically control weeds.

General rules of mechanical weeding

The success of all mechanical weeding systems is determined by weather, with the best results being achieved in warm, windy and dry conditions which help the weed to die rapidly after the weeding pass. If these conditions are not met, the weeds can often simply become transplanted further along the row. However, if conditions are really dry, the weeding process can cause stress on the growing crop.

The action of passing a weeder through the soil results in some nitrogen mineralisation which has been estimated to generally be between 10-35kg/N/ha. This can be a useful nutrient boost to the growing crop in the spring, especially in organic management systems where nitrogen can be limiting at that time of year. But, the very process that leads to the nitrogen mineralisation also results in the death and disturbance of soil organisms and the oxidisation of soils results in loss of soil carbon.

Broad spectrum mechanical weed control

Tine weeders are available for agricultural use from 6m to 24m wide machines. Generally they are highly adjustable machines which allow for a range of tine widths and angles and this determines how aggressively the tines are pulled through the crop. Working speeds are relatively fast at about 10kph allowing for fast coverage of cropped area and potentially allow for several weeding passes in the same growing season.

The timing of weeding operations is really important and the final tine weeding must be completed before growth stage 31 in cereals or before stem extension in broadleaf crops to avoid unnecessary damage to the developing crop. It is important to get into a growing winter crop early in the New Year as weeds tend to grow very fast with lengthening days and increasing soil temperatures. There is always a compromise to be made between the weeding time and the risk of further weed emergence but big weeds are far harder to mechanically remove as there are far more resilient.

Tine weeders tend to be used in the same direction as the crop rows as running at an angle or across the rows would cause greater stress on the growing crop.

Inter-row weed control

This is an area where a great deal can be learnt from the horticultural sector which has a longer history of weeding between crop rows. Machines such as the Garford Robocrop have camera row guidance systems to enable more accurate and faster work rates thereby avoiding crop damage. Guidance systems on inter row hoes rely on being able to clearly recognise individual crop rows and therefore require row spaces of at least 20cm to define the rows. These systems also tend to work better when the drill width is matched to the inter row hoe width so any curves within the drilled rows is the same across the working width of the machine. It also helps to drill using GPS to keep rows straighter to aid the camera keep to the straight rows. Another really important factor is that there has to be more crop in rows than weed for these camera guidance systems to function successfully. Using camera guided inter row hoes in the weed scenario above would cause great challenges due to the narrow row spacing and the high weed population.

Other mechanical weed control options

Machines such as the CombCut or Weed Surfer work above the crop canopy and only cut weeds that are taller than the crop. Many weeds do not have a great enough height deferential to be effectively managed by this method. For those weeds which do grow taller than the crop, this height difference often does not occur until later in the growing seasons when weeds may have already caused some competition for light, water and nutrients with the crops. However, these machines can be a useful tool in preventing weed seed return and thereby help prevent greater weed challenges in subsequent crops.

These machines do not remove the weeds from the site and therefore they are most effective either prior to or during early flowering to prevent viable seed set. These systems do not uproot or fully remove the weed and are often used alongside other weeding techniques.

How many passes?

This is always a difficult question to answer as a mechanical weeding process can stimulate further weed germination and therefore increase weed burdens. Generally the important issue is to control the weeds before they become too big and this can involve making passes earlier in the growing season to avoid weeds becoming challengingly big. Early passes can be difficult to conduct in winter crops due to wet field conditions but can potentially be conducted when there has been a light frost to enable the field to travel.

The cost of mechanical weed control

Contractor prices for mechanical weed control are not clearly determined and in many areas there is still a lack of availability. As with many contractors’ prices, the actual price is defined by the amount of opportunities available in the area for mechanical weeding but also on the amount of hectares to be weeded.

Mechanical weeding Approx. contractor technique costs (£/ha)

Tine weeder 22

Inter row camera guided weeding 45

Above canopy weed removal 30

Mechanical weeding results

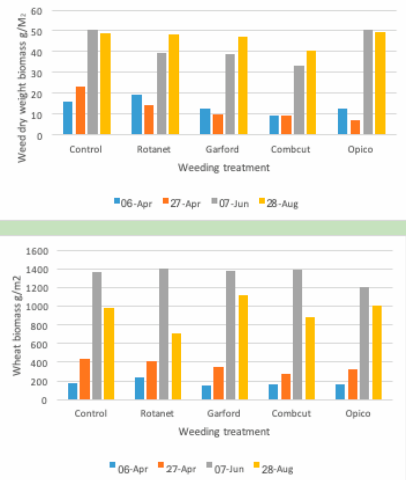

Trials conducted on the Royal Agricultural University’s farms in 2017 growing season showed relatively poor control of weeds through mechanical weeding. But, it has to be noted that this year suffered a very severe spring drought which really impacted crop growth over all the farm. Weed populations really developed when the rain eventually arrived in mid-May.

These trials were conducted under organic farming conditions, so no herbicides were used to assist in weed control and the crop was a second winter wheat which with a very high weed seed bank. Neither weed biomass or wheat yield were influenced by the weeding treatments due to the large variability in weed populations over the large plots sizes.

Conclusions

Mechanical weeding can reduce weed biomass but weeds can recover and mechanical weeding will only work if used in conjunction with other agronomy techniques to reduce weed populations.